Webinar

COVID-19 and the Legacy of Racism: Vaccine Hesitancy and Treatment Bias

Time & Location

The COVID-19 pandemic’s devastating impact on Black, Latino and other communities of color has resulted in disproportionately high rates of cases, hospitalizations and deaths. Racism, both historical and current, complicates efforts to reduce these disparities by contributing to vaccine hesitancy, treatment bias, barriers to testing, and ongoing economic and social inequities.

Part of the series, "Stopping the Other Pandemic: Systemic Racism and Health," this webinar explored challenges and solutions.

Speakers discussed:

Addressing vaccine hesitancy in Black and other communities with significant health disparities

How race-based treatment bias impacts care and health outcomes for Black and other patients from communities of color and how to bring about positive change

A health plan’s efforts to ensure access to culturally competent care, support and educate its members about COVID-19 testing, and improve access to primary care

View the first two webinars in this series to learn more about the impact of systemic racism and inequities on Black and Latino health.

Sheree Crute (00:00):

Good afternoon. I am Sheree Crute, director of communications at the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, NIHCM. On behalf of NIHCM thank you all for joining us today to explore some of the most important issues affecting the health of Black, Latino, Native American and other underserved communities during the most challenging health crisis of our time, the coronavirus pandemic. Our goal today is to look at the connection between historical and current forms of discrimination, past and current health care system inequity and the ongoing disparities we see today as they relate to people receiving the COVID 19 vaccine, equitable COVID-19 treatment and having access to testing.

Sheree Crute (00:47):

While everyone is at high risk for COVID-19, statistics continue to show us that Black, Latino and Native American people contract the virus at higher rates, experience more severe cases and die from the disease in larger numbers than white Americans. There are many factors contributing to this scenario, but today we're going to look at treatment bias in health care and how it relates to new issues that are emerging now that we have a COVID-19 vaccine.

Sheree Crute (01:17):

Just yesterday for example, the Kaiser Family Foundation released data showing a consistent pattern of black and Hispanic people getting a much smaller share of vaccines than white Americans. Vaccine hesitancy may be part of the issue, but an emerging problem is a lack of access to the vaccine in Black and Latino communities. Disparities are so high that mayors in Washington DC, New York and other cities are taking action to change distribution pattern. The barriers to addressing this situation and others are significant, but not insurmountable. The panel of expert speakers we are fortunate enough to have with us today are going to help us to understand these issues better, offer strategies and solutions for clinicians, policy makers and others working at the federal, state, local and community level.

Sheree Crute (02:09):

Just before we hear from them, I want to take a moment to thank NIHCM's president and CEO, Nancy Chockley and the NIHCM team who helped convene today's event. In addition, you can find full biographies for our speakers along with today's agenda and copies of their slides on our website. We also invite you to live tweet during our event using the hashtag treatment bias. We will take questions, as many as time will allow, after our presentation.

Sheree Crute (02:40):

I am now pleased to introduce our first speaker. Dr. George Mensah is division director at the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Center for Translation Research and Implementation Science, at the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mensah leads an integrated effort to advance the translation of scientific discoveries in heart, lung and blood diseases research to clinical and public health practice, nationally and globally. In addition to his years of service in public health at the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Mensah's an expert on health disparities in public health. Today he's going to help us understand the complexity of vaccine hesitancy in high-risk populations and some disparities. Dr. Mensah.

George Mensah (03:31):

Sheree, thank you very much for the wonderful introduction and I should say that it's real pleasure for me to give this presentation on behalf of our NIH wide community engagement alliance against COVID-19 disparities. This is an initiative that we call the seal initiative. First, let me also express our gratitude for the NIHCM leadership and staff for thinking about including us in this important webinar.

George Mensah (04:12):

What I'll try to do in the next 10, 15 minutes is first set the stage so that we're all using the same terminology. I like to define just a few things and then delve a little bit more deeply into vaccine hesitancy. The NIH strategic plan on minority health and health disparities was just published and I referenced the categories of rates and the definitions of minority populations. The four categories shown here, what we now recognize as the mission ethnic minority populations, categories by race. It's important to highlight that not all of these four have been disproportionately impacted and as Sheree mentioned at the beginning, American Indian, Alaska native, black or African-American, native Hawaiian or other Pacific islanders have been the most impacted within these four. We also recognize categories by ethnicity and of course there are individuals who disclose two or more race categories. The panel on the left shows you what we're talking about, that huge and disproportionate impact on some racial and ethic minority groups. Comparing the rate per 100,000 population. You see the substantially higher rate in American Indian or Alaska natives, in black and Hispanic, compared to white and Asian or Pacific islander groups and in the panel on the right we highlight that this is a result of an interplay of several things, including clinical characteristics, a very, very important component of social determinants of health and very often exposure to the type of work that individuals do, as well as access to care as was mentioned. This next slide actually puts these in numerical context. If you look at the number of cases, you see in American Indian or Alaska natives where you have nearly a fold increase and in black and Hispanic or Latino persons, one and a half to two-fold increase. Hospitalizations are substantially higher. In American Indians almost a four-fold difference compared to white. Again, black or African-American and Hispanic or Latino persons, also three and a half to four-fold and of course we know about the mortality differences, almost two and a half to three fold greater rate of death in American Indians. Similarly high 2.8 to three fold greater in blacks and Hispanics. Vaccine hesitancy is very common, but it's also a continuum and in this image we define it as the area in the red box. That's the area between individuals who are ready and willing to accept a vaccine right away, they are shown in the green and at the very other extreme is individuals in the red who are very clear, they don't want to have anything to do with the vaccine, but we have a huge opportunity represented in the box. These are individuals who are not sure, maybe they want to wait to see other people get the vaccine, but then they will take it, all the way to the other end where they don't want it at all now, but maybe they will change their mind. We see it as a unique opportunity to provide trustworthy, consistent facts and evidence-based information, so that we can help them make the right choices in accepting the vaccine. It's a spectrum between those who completely accept and those who completely refuse, but we shouldn't really exclude anyone. We should make sure we provide the information to as many people in the red box as possible so that we can increase the number of people who accept. There are many reasons for vaccine hesitancy. I've listed here four that are very important. There may be questions or concerns about benefits and safety or side effects and for others, it may be concerns about the speed with which the vaccine has been developed. They want to know if any corners have been cut. There are others who are hesitant because they distrust the system and including even the government and the companies involved and finally, there's just rampant misinformation from conspiracy theories, about sometimes just factual inaccuracies. We all have a public responsibility to be patient and answer all the questions and provide information so that the concerns can be allayed.

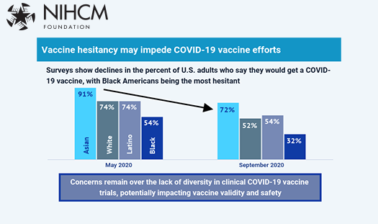

George Mensah (09:57):

Why is this important? As you see here, the national trend suggest that if you look at the proportion or the percentage of US adults who say they're likely to get the vaccine, from the period of April earlier this year through until most recently, that trend of the number of respondents willing to accept it, has being going down and that should be a concern to all of us. I will show you several slides that actually demonstrate that. This national trend may actually mask important differences at a racial and ethnic minorities level. In this JAMA paper, if you take a look at the bottom of the table, where we should race and ethnicity, I've highlighted in yellow, showing that back in April only about half of African-Americans were willing or likely to get the vaccine, but by the November, December period, that had gone down as low as 37%. The proportions for the other racial and ethnic categories are shown.

George Mensah (11:11):

This next slide makes it even more serious and why we all need to do our best to try to change this. The vaccine intent is lowest if you look in the bottom green, only 12% say that they would definitely intend to get the vaccine. It's also lowest in young people when you look in the hesitancy by age group. The lowest 22% in those age, 18 to 34.

George Mensah (11:48):

I've shown you in this survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation, showing in green is those who are ready to roll up their sleeves and get a vaccine as soon as possible, but at the very end of the chart you see the 15% for total US level of the survey and 15 to 18% for black, Hispanic and white, but the most important thing I want to demonstrate here is if you look at African-Americans, almost two thirds were vaccine hesitant. About half of Hispanics were vaccine hesitant. This is the challenge that we face that we want to make sure that we can address. There is some good news, but all that good news suggests is every effort we make is likely to be very successful, but we have a lot of work to do. In that period that you see here from September to December, in African-Americans, the acceptance or the willingness to accept has gone up from 50 to 62%, has gone up in Hispanics, it's gone up in everyone and that's a reflection of the work that all of you have been doing. We just need to do more and more so we can get to the 80, 90% aspirational goal.

George Mensah (13:11):

Here are some important concepts that we have to take into account so that we can successfully address vaccine hesitancy. One size definitely doesn't fit all communities. We must contextualize our efforts to specific communities and all of the work must begin by listening. Listening to the community's needs, their concerns and that listening exercise will help us tailor and contextualize efforts. A very important strategy to use is to address the three Cs. This is the three C model that looks at confidence, it looks at complacency and it looks at convenience and I've highlighted trust because it's foundational to confidence. We must elicit what goes into the distrust and do everything possible to address that. Complacency, some people believe that maybe COVID-19 is not that serious. It might even disappear on its own. We all know it is not. We need to take steps to listen first and put in place mechanisms that address their complacency and certainly making sure we can direct people to where the vaccine is available. We have to make sure we understand we can't do this alone. We have to work in partnership. Certainly counting on trusted voices and trusted messengers is key and they vary in different communities. In some communities, it may be the doctors and nurses. In other communities it may be the pharmacist, it may the clergy and other faith based organizational leadership. There are volunteer organizations that have been...

George Mensah (15:03):

... Organizational leadership. They're volunteer organizations that have been working in our communities for a long time, have a strong track record, and they may be the trusted voices. We have to realize that we should not try to do this work alone and we must work in partnership with these trusted voices. In my one or two final slides, I've summarized here some of the effective communication strategies and tools that we can use, and other mechanisms and strategies for building trust. We really have to take all of these into account and make sure that we are likely to be successful.

George Mensah (15:40):

Before I get to the website, showing you where we have teams in the U.S, working on addressing vaccine hesitancy, working on addressing inclusive and diverse participation in all our efforts. And we are very eager to share with you everything we have learned so far. The teams in our states are also very, very eager to help. Here is the website for our Community Engagement Alliance, and it's covid19community.nih.gov. I'll finish with this a takeaway message, that vaccine hesitancy is important, is dynamic, therefore it can change. But that change requires community engagement, it requires effective outreach, it requires building trust, and helping understand the vaccine process, and most importantly, always, always, always sharing truthful information. I will stop here and turn it back over to Sherry and say thank you very much for including us in this important work.

Sheree Crute (16:59):

Thank you so much, Dr. Mensah, for that comprehensive analysis and the extremely valuable solutions to the problem, and those slides, which will be on our website after the event. Our next speaker, Dr. Lauren Powell, is the president and CEO of the Equitist, and serves as vice president and head of Time's Up Foundation's healthcare industry work. In this role and through her work in her company, the Equitist, she spearheads national efforts to champion health equity and eradicate racism and sexism from healthcare workplaces. Named as one of Fortune Magazine's 40 under 40 in healthcare in 2020, Dr. Powell is an outspoken advocate about racial injustices and health inequities, and has led equity efforts in healthcare, state, government, academia, and public health. Today, she's going to delve a little deeper into why we perhaps have issues with trust, and to help us understand the legacy racism that has in part shaped many of the disparities we confront today. Dr. Powell?

Lauren Powell (18:07):

Good afternoon, Sheree, and good afternoon to everyone. Thank you so much for the invitation to be here today. And thank you also for hosting this really important discussion. Let me first make a slight edit to a couple of words that you said. I actually work for a different organization at this time. I work for Takeda Pharmaceuticals, and I will not be representing them today. But I did need to disclose that, that my remarks today or my personal opinion will be shared through the lens of my role as president and CEO of the Equitist, which is a boutique consulting firm focused on operationalizing health equity in public health, healthcare, and beyond. So today we're here to discuss the legacy of racism in race-based treatment. So this will be a vignette of experiences and milestone moments that have shaped the legacy of racism and its impact on race-based treatment in healthcare.

Lauren Powell (18:58):

First, I think it's important that we center our discussion first with the definition of racism. So, leading scholar Dr. Camara Jones, I like her definition. She describes racism as a system of structuring opportunities and assigning value based on a social interpretation of how one looks, which is what we would call race. And that unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities, unfairly advantages other individuals and communities, and overall staffs the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources. So the question is, how did we get to this classification? Well, to get there, we really need to go back into history a bit. We know that some 400 plus years ago, in 1619, the first group of African captives originally [inaudible 00:19:51]. What we know now as modern-day Angola arrived to the then colony, but now Commonwealth of Virginia. This would mark the beginning of hundreds of years of torture, of slaughter, and of annihilation of black people in America.

Lauren Powell (20:07):

For some 180 plus years, the importation of slaves was permitted in America. But in roughly 1807, a United States federal law called the Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves was passed, and it was an act of the following year. So technically, it says that no new slaves are permitted to be imported into the United States. So, I want to first pause and I want us to think about the language that's being used here, and remind us that we're talking about actual people here. So, this entire population of people who were seen and treated as good. So, to that end, the 1807 Act Prohibiting the Importation of Slaves, presented a challenge for slave owners. So, prior to this, they could replace aging or injured bodies or slaves with newly imported ones. But this act made that a bit more complicated, technically. This shifted their focus from importing slaves, to procreation and using the slaves that they had to procreate and create new ones. So, there was now a new invested interest and focus on keeping particularly women of childbearing age, healthy and alive.

Lauren Powell (21:28):

If we fast forward, just a little bit, the early 1850s to the mid 1900s. We're going to jump into eugenics and scientific racism. Now this all goes together. Eugenics was the process of improving the genetic quality of white European races by removing people deemed inferior. So several scientists, Carla Marisson, Arthur Digabino and many other scientists, they gave rise to scientific racism. That is a fallacy argument that created the alleged empirical evidence to support or justify racism based on all these physiological features. So cranial size, or nose size, or shape, even skin color or tone. This gave rise to the overarching notion that black people in particular were inferior. Eugenics is often associated with the genocide of the Holocaust. But many of these foundational teachings started in the United States and were aimed particularly at black people.

Lauren Powell (22:39):

Now, creating a narrative about black bodies as commodities or goods as a result of slavery and black people as being physiologically inferior as a result of eugenics, paved the way for an era of experimentation on black bodies that ultimately built modern medicine. So, when we think about the history of experimenting on black bodies, we could start sort of with, the widest is Mrs. Henrietta Lacks, who is a black woman who cells were harvested without her knowledge or consent, but went on to create the first human cell line. Her cells are known and were used for years under the abbreviation of HeLa cells. HeLa stands for Henrietta Lacks. And her cells are still alive today. And they've contributed to creating everything from the polio vaccine, to the HPV vaccine, which ironically, if it had been around when she was diagnosed with cervical cancer could have even saved her life. And while her cells have been used very widely for medical breakthroughs and discoveries, her family and her descendants who are still alive today, remain largely uncompensated for her contribution. But she is the matriarch of modern-day medicine. Other examples of experimentation on black bodies include, if we go from the top corner of the slide across, the experiments of Jay Marionson, who was often heralded and regarded as the father of gynecology, who conducted his experiments on African enslaved women, the names of whom are largely unknown, with the exception of three, Lucy, Enarca, and Betsy. It's said that he performed procedures that are still used today on his subjects, as many as 40 times without anesthesia or pain medication. Now it's important to remember that. In a few slides, we will talk more about how pain is regarded in black people who seek healthcare treatment. And the next two pictures that are sort of diagonal to each other, you'll see the experimentation was not only relegated to the living, but also to the deceased. Body snatching, particularly from black cemeteries, because they were segregated was a practice by medical schools. In order to have cadavers for anatomy and physiology courses, schools employed, quote, "Resurrectionists" to feel the bodies of black people under the guise of medical advancement and learning, again, without their consent, oftentimes without their knowledge.

Lauren Powell (25:28):

So, families would just go to visit a grave site and see what it was empty. The most infamous of these examples though, is the bottom corner, is the United States Public Health Service Corps Commission study of untreated syphilis in black men at Tuskegee University in Macon, Alabama. Most notably, it was an unethical natural history study. It was conducted from 1932 to 1972, in which the purpose of the study was to observe the natural history of untreated syphilis. So. going back to the connection of eugenics, the whole purpose of this study was to see if syphilis operated the same way in black bodies as it did in white bodies. So still this undercurrent notion that somehow black people of black bodies were inferior. The black men who participated in the study were told that they were receiving free healthcare from the federal government. But when a treatment, penicillin, was discovered in 1947, it was not offered to the men. And so, you could imagine there were several generations own lineages following throughout their families that definitely were impacted by these decisions.

Lauren Powell (26:53):

And it is there that people really sort of hang their hat. When we talk about mistrust, people really often go back to the study of Tuskegee. And while that is an example, there are several others, and there are more recent examples as well. We think about sort of the history and the legacy of unequal treatment. In 1999, Congress commissioned that study focused on health disparity. They wanted to better understand racial and ethnic health disparities in healthcare. And what they found largely, was that racial ethnic minorities have benefited less from overall improvements in America's healthcare system, that despite interventions to equalize population health, that disparity still existed with within racial and ethnic minority populations. The quality of patient care was not the same, and that the differences in health outcomes were based on racism and discrimination faced when seeking healthcare. So, this was in the late '90s, early '2000s.

Lauren Powell (28:05):

And you might ask, "Well, have things gotten better?" Not so much, not quite. It's important to note that mistrust is not really just about what happened 40 plus years ago. It's not about everything that's happened seemingly in the past. It's also about what's happening right now. I pulled these headlines from recent articles. A black man, just a few days ago, died in a parking lot outside of a hospital. And his widow says that the hospital refused to treat him, a 39-year-old black man. Studies on how COVID-19 is having a harrowing impact on young black men. Studies and reports about how COVID-19 is having a disproportionate impact on the Native American community, on the Latino community, on vaccine distribution and major barriers to those populations trying to seek healthcare and trying to be treated equitably.

Lauren Powell (29:17):

The years of medical exploitation and denigrated treatments in the name of medicine have led to a rightful sentiment of mistrust in healthcare systems and providers. But I think it's important that we're hearing so much about mistrust. And to me, mistrust, the definition of it literally is to be suspicious of, or to have no confidence in. I think that, that lies so heavily on the shoulders of individuals. This one sided, and places the shoulder of blame on individuals that to somehow become more trusting. And it really absolve us of the challenge of thinking about why people don't trust. Where perhaps we should shift our-

Lauren Powell (30:03):

... why people don't trust. Where perhaps we should shift our thoughts to trustworthiness, which is literally the ability to be relied on as honest or truthful. Trustworthiness puts the onus back on healthcare entities and healthcare organizations to behave and operate in a way that makes them trustworthy.

Lauren Powell (30:28):

It's important to note that the impact of biased treatment in healthcare still remains today. That as recent as 2016 and probably even more recent than that racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations and the false belief that essentially black people have thicker skin still prevail among medical students, among medical trainees. That medical mistrust and racism caused delays in preventative healthcare screening among African- American men and women. And that it's still results in differences in health outcomes, differences in life expectancy. And those have monumental impacts on populations.

Lauren Powell (31:18):

I think one of the most prevalent examples of race-based treatment is the recent story and tragic story of Dr. Susan Moore, a black physician who went viral with a video that she made from her hospital bed, from her deathbed, explaining that she felt that she was being treated unfairly because she was black and because she was a black woman. There was a quote from the video that the physician made her feel like a drug addict. She accused the white doctor of downplaying her complaints of pain and suggesting she should be discharged. This story has been so harrowing throughout the black community, throughout lots of the healthcare community, lots of communities. It's left people with this question, if a well-educated black woman who is also a physician was treated this way, what would happen to the rest of us?

Lauren Powell (32:18):

It is that mistrust. It is that level of a lack of trustworthiness, perhaps in the healthcare industry that is contributing to things like vaccine hesitancy. But it's so important to also recognize that this happens everywhere. It's not just in healthcare. But race-based treatment by police and the American judicial system, as we've seen in the egregious assassination of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others that racism and xenophobia aimed at Latinos, Muslims and native Americans. It's important that healthcare leaders and public health leaders understand that race-based treatment or racism is a holistic experience when it comes to American society. So, feelings of mistrust are not relegated to healthcare alone. Racism happens when people are seeking housing, seeking jobs, seeking educational opportunities, grocery shopping. It permeates so many different parts of society, but it's so important I think to remind people that it's racism, that's the problem, and it's not race. As in, it is a system that is biased towards different groups that makes this a problem.

Lauren Powell (33:36):

It is not the fact that people are from different races. And so, I like to always conclude my remarks with some actions, because I think it's so important that people walk away with something to be done. So, what can we do to stop racism and race-based treatment in healthcare? Detection, I think it's 4D. So, detection, I think it's important to leverage data, to highlight the problem we think about vaccine hesitancy. Well, the fact that we don't have enough racial and ethnic data to know how vaccines are being distributed, it's certainly important and certainly also problematic. Discipline, that there has to be real accountability for healthcare leaders and for providers who engage in race-based treatment. There must be a dedication of time, resources and personnel to combat this as an issue. And that there must be determination behind this. It cannot be a quick turnaround. It cannot be a quick fix. It has to be a long-term commitment to change.

Lauren Powell (34:45):

And ultimately, I'll just say, I'm so glad that we're talking about this. I think it's really, really important to understanding some of the roots of vaccine hesitancy, but I certainly think as Dr. Mensah sort of covered in his presentation that there are ways to overcome this that are rooted in community voice, that are rooted in elevating community voices in working hand in hand with communities to establish trustworthiness as healthcare entities and organizations. With that, thank you for your time and attention and happy Black History Month to you.

Sheree Crute (35:24):

Thank you so much, Dr. Powell for that powerful and enlightening, look at our history and fresh perspective on how to address some of these issues. Now, I would like to welcome to Dakasha Winton and Dr. Andrea Willis from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee. Ms. Winton is senior vice president and chief government relations officer for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee.

Sheree Crute (35:49):

She leads the company state and federal government relations efforts and oversees analysis of proposed legislation. She serves as the Blue Cross liaison to federal and state industry associations and advocacy groups. Dr. Andrea Willis is senior vice-president and chief medical officer for Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee. Dr. Willis ensures that all of the company's clinical initiatives contribute to the overall health and wellbeing of the communities they serve. Under the leadership of JD Hickey, president and CEO, Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee is committed to a culture of diversity. And the company has stated that it stands in solidarity with their partner communities, our members, and our business partners against racism, especially during these difficult times.

Sheree Crute (36:38):

A key part of this work is the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee Foundation's recent grants for research at the Meharry Medical College's Center for the Study of Social Determinants of Health. The grant will fund research by the nation's largest private historically black academic health science center on barriers to healthcare, poor health outcome, and vaccine hesitancy in at-risk communities. Ms. Winton and Dr. Willis will discuss how they're solving these problems at the state level in Tennessee.

Dakasha Winton (37:10):

Thank you so much for that introduction. And on behalf of our over 7,000 employees and the three and a half million members we serve, we want to say thank you to the NIC and staff and all of you for being here with us today. Oftentimes we are having health policy discussions, like the one we are having today, the last place people look to for an opinion is to their health insurer. Now, we hear all of the other things you say, insurance costs too much. It doesn't pay for anything insurance companies always say no. And while we obviously disagree with that sentiment and love to share our viewpoints on the actual cost drivers of health care, that's a topic for another day. One thing that I think that we all can agree upon is that insurance companies have a great deal of data. And we have a great deal of data because we process a tremendous amount of healthcare claims. And through that data, we hope to offer a different perspective than what you would normally hear in these types of discussions.

Dakasha Winton (38:09):

Thus, I am happy to introduce my friend and colleague, Dr. Andrea Willis. She will share with you some of the things that we've learned at Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee using the power of data, emphasizing the clinical perspective, recognizing the historical context and understanding that forming strategic partnerships driven by data can provide policymakers, clinicians, and individuals, the tools that they need to change healthcare outcomes, particularly for people of color. Dr. Willis?

Andrea Willis (38:40):

Thank you so much, Dakasha. And thank you for the opportunity to talk about public health and specifically, what we view at the health plan's role in public health. I have been in private practice, worked in the public, and now in the private sector. I have learned great lessons from each experience, but perhaps the greatest lesson is that every sector must play a role in public health, and where those roles intersect around that human life should be singular in purpose and create a synergy so dynamic that we are all the better for it.

Andrea Willis (39:19):

One of my favorite quotes is from Dr. William Fegi, a former chief of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. He said in the speech to graduate in medical students, " There is something better than science, and that is science with a moral compass science that contributes to social equity. Science in the service of humanity." I think he was right. And I think this COVID pandemic well illustrates that we are in a place in time where we collaboratively need to make sure everyone benefits from the science realized through health care. This slide is just a snapshot of data that we as a health plan have within our reach. This was last year and before we saw the big peaks of COVID-19 infections. The point of this slide is that even though this is strictly claims-based information and it does not nearly show all of the public health picture, it is still a piece of the puzzle that gives an additional perspective. The more important point is even within this sliver of information, we see health disparities.

Andrea Willis (40:37):

These are things that we did as a company to address health disparities. I'll highlight just a few. We funded free COVID-19 testing for uninsured and under-insured communities. We financially supported, increased broadband access and underserved areas. We have produced media for both flu vaccines, and now COVID vaccines with intentional focus in minority communities. We have increased the number of scholarships we've awarded to minority students, pursuing healthcare professions. Our foundation just last week, issued a request for proposals for community grants, to support grassroot efforts to promote COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. We do realize that we can't do it alone and that there is power when we, we meaning the public sector, the private sector, the provider community, trusted community partners and policy makers work together.

Andrea Willis (41:41):

In 2020, we really had two pandemics. We had COVID-19 as well as the magnification of racial injustices. Those things together, really exacerbate health disparities. The true heart of public health is making sure we take care of the most vulnerable. In doing so, we strengthen the entire system for all. And that's why we are honored to partner with Meharry Medical College to really try to dance the work around health disparities. And I'll talk more about that in a moment.

Andrea Willis (42:22):

Social determinants of health include differences in factors like social economic status, education neighborhood, and physical environment, employment and social support networks, as well as access to healthcare that contribute to differences in health and healthcare. And I'll just say addressing social determinants of health is so important, because it makes us examine those things that have happened historically and continue to happen that contribute to the lack of resources to protect health. Personal responsibility is certainly important in health, but the question becomes, what are the barriers in place that impede certain segments of the population from even having interactions with healthcare providers and from receiving culturally competent health education that can inform that personal responsibility?

Andrea Willis (43:21):

Last year, representatives from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee and Meharry Medical College would often find themselves in the same virtual meetings, talking about how COVID-19 was disproportionately impacting minority communities. Meharry is the nation's largest private, historically black academic health sciences center. They are well-respected in their service to disparate populations.

Andrea Willis (43:48):

And while both Blue Cross of Tennessee and Meharry will continue our respective efforts on health disparities, we recognized that there was opportunity for exponential impact if we work together. Meharry brought leaders from several of their programmatic areas to the table. The joint collaboration focuses on the goals of examining COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and the underlying reasons that contribute to it. So while this focus is on a right now problem, we believe it will have broader applicability to address health disparities and distrust of the healthcare system. So, this slide is an illustration of the skepticism that exists around the COVID vaccine. It's taken from the Kaiser Family Foundation and it just echoes something you saw earlier. This snapshot shows that young people, then black adults followed by Hispanic adults, have a wait and see posture when it comes to the COVID-19 vaccine. This slide goes into a little more on how we will combine data with Meharry to build a more comprehensive picture.

Andrea Willis (45:03):

Data is so important because it is the common language that speaks to improvements in outcomes. It also objectives points where we've missed the mark, and where there are opportunities. At BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee, we utilize the Social Vulnerability Index to improve our outreach strategy to the communities being disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. Our collaboration with Meharry leverages that, and builds upon it by further identifying high-risk communities by applying predictive modeling. It helps to prioritize those communities, not only for the vaccine, but to build the supports needed to address the ongoing social determinants of health in those communities as well.

Andrea Willis (45:53):

Data certainly strengthens the talking points when bringing other stakeholders to the table, like policy makers and providers. It can be the report card we hold up to show how the healthcare system is doing, and it can help guide where we need to go.

Andrea Willis (46:12):

These are the dimensions of the Social Vulnerability Index, scores are assigned based on factors such as safety, food insecurity, housing, healthcare access, and health literacy, among others. A higher score means more negative impact to health. Social vulnerability is not just a score though, it refers to the ability of communities to be able to withstand external impacts to health. In other words, it evaluates how outside forces, such as disasters or disease outbreaks further compound the odds already stacked against these communities.

Andrea Willis (46:54):

If the totality of those odds are too high, it leaves very little opportunity for those communities to overcome the odds, and even less opportunity for them to decisively win an already uneven fight.

Andrea Willis (47:12):

I'll wrap up by saying that we as an industry often talk about quality metrics that support the very ideal of better health, that is what the focus of healthcare should be in general. And it is absolutely what should be demanded for those that feel that the healthcare system has forgotten them.

Andrea Willis (47:32):

As we look back on 2020, I think the questions that we have to ask ourselves are, what have we learned, and what are we still learning that will make us better? And perhaps even more importantly, what are we committed to keep learning going forward?

Andrea Willis (47:52):

This crisis has called upon all of us to do our parts to weave together a better public health response. We need to invite non-traditional stakeholders to the healthcare table, like trusted community partners if we really want to make a difference in this fight. The healthcare system has been moving towards value-based care, that's based on quality measures and outcomes. My hope is, is that the steps we take to address social determinants of health for disparate populations becomes embedded in those value-based metrics so that it becomes institutionalized. We are all a part of public health. Thank you.

Sheree Crute (48:40):

Thank you, Dr. Willis, and Ms. Winton for such a comprehensive picture of disparities and their impact on public health. Very quickly, we're going to try to ask our speakers to respond to a few questions. I apologize, hundreds of questions were submitted. And so, the best we can do is to try to aggregate some of those that were asked many times.

Sheree Crute (49:03):

My first question is for Dr. Mensah, it's a combination of several questions. What do I say to my patients that tell me if you do not trust the vaccine, because it was made too fast, and it was a rushed process? What is FDA approval and the science behind the vaccine? Those questions are made together. Dr. Mensah?

George Mensah (49:27):

Sheree, it's a tough question, but it's a very important question, and one that we have to make sure we respond to.

George Mensah (49:38):

First, these COVID-19 vaccines we have in the U.S. have been amongst the most rigorously tested, using standards of safety and efficacy, that we know about. So, there were no corners cut, they all underwent very rigorous testing. Second, the technology and the platforms for developing these vaccines have improved tremendously, even compared to three or five years ago. But the most important reason why we're able to get these vaccines done in such a short time, have to do with a few things. And I'll mention about two or three of them. In the olden days, the way you developed a vaccine was you start with bench research. You work in animals, you work in cells, that could take up to three years. Once you have a candidate vaccine, then you test it in humans for safety, it could take six months to a year. But you wait to get your results, and if it turns out to be safe, then you go to phase two where you figure out, "Well, how much of it is needed? Do you need to give one dose or two doses?" That could take a year or longer. You finished that study, you get your results, sometimes you publish the results, you go to the FDA, then you begin your phase three.

George Mensah (51:09):

So, all of these are done in sequence. You finish one, and then you start the next. So, you start with two to three years, and another year here, you're talking five to seven years. The final thing that was also very important is that in the olden days, you recruit say 4,000 participants, 2,000 get the vaccine, 2,000 get a placebo, then you wait two to three years to see how many in the placebo develop the disease, and how many on the vaccine developed the disease. So, you can figure out how much better is the vaccine than the placebo.

George Mensah (51:47):

Well, what did we do differently? What we did differently was instead of doing things in sequence, we did all of these processes in parallel. Meaning at the time that we designed the phase one study, we have people designing the phase two study, and designing the phase three study. Well, what do you lose? There's a lot of money and staff time that you put to it. But if the phase one study doesn't demonstrate it's safe, all you've lost is just money. You don't lose any time at all.

George Mensah (52:20):

In addition, even before the phase three studies are completed, you start building the factory to start manufacturing the vaccine so that if the phase three study is successful, all you do as ramp up and produce millions of doses; you don't wait to complete the phase three study before you start building the factory.

George Mensah (52:41):

Now, all of that was possible because of billions of dollars that the federal government made available to guarantee so that private sector that were bold enough to get into the vaccine business would not go bankrupt if things don't work out right.

George Mensah (52:58):

But every step of the way, what was guaranteed was the safety. So, doing things in parallel, rather than in series, having an FDA that was ready and eager to make decisions within days, rather than have people join the queue and wait four weeks to a month before the issue comes up, all of that collectively made it possible for us to go fast.

George Mensah (53:24):

The last thing I would mention is if you look at the phase three studies, where in the past you would recruit a couple of thousand people, say 4,000, and these COVID vaccines, we recruited 40,000, so that instead of waiting three years, you only need to wait 10 months to have enough conditions.

George Mensah (53:47):

So, safety was always guaranteed, and it was a reflection of improved techniques and platforms for developing the vaccine, and strong support from federal government, so that the industry can be bold. I'll be very happy to send you additional information if you write to us, but the active partnership that we've put together of a public-private partnership with strong support from the federal government made all of this possible.

George Mensah (54:17):

So, we didn't cut any corners at all. And in fact, these vaccines are among the most rigorously tested, and they are safe. I will take it myself. Thank you.

Sheree Crute (54:29):

Thank you, Dr. Mensah. I think we have time for one more question. Again, a combination, I'm directing this towards Dr. Powell, how can media policy and other public sources of information address embedded cultural beliefs, and recent racism in other communities of color, to help support greater trust among medical, for medical and public health efforts and expert?

Lauren Powell (54:57):

Well, thanks Sheree for that dissertation-level question. I appreciate it.

Lauren Powell (55:04):

I think that is a very complex question, but I think first and foremost, elevating the truth is really important. I think it's also about the message, the message as well as the messenger. So elevating messages that incorporate and uplift equity, that shine a spotlight where there are inequities, and also ensuring that we have messengers that are diverse. So, ensuring that we have diversity in media, ensuring that we have diversity who our storytellers are, as well as who our spokespersons are. I think all of that goes together and works together to build better platforms of trust, and better platforms that really elevate the diversity of America, and shows the many different facets and many different ways that vaccine hesitancy, or just the vaccine is impacting different communities.

Lauren Powell (56:05):

But I also think it's important to recognize none of us, or none of our communities are monolithic. So, all black people, for example, are not mistrusting of the healthcare system. We have to be careful not to over-generalize. There are lots of people of color who want to take the vaccines, who want to get vaccinated, but the vaccine is not available to them; the vaccine is not within reach. It is within sort of a mass testing site, or something that they're not able to necessarily access. So, I think we also have to be careful, even in our messaging, not to over-generalize, to assume that just because some of it is from a marginalized community or group, that they're not interested in the vaccine.

Lauren Powell (56:50):

I think that goes, again, to the fact that our systems need to create themselves to be more trustworthy, and not just put the burden of trust on the backs of communities and community members who have been marginalized previously.

Sheree Crute (57:09):

Thank you so much, Lauren. I am not sure we have time for another question. So, I am going to wrap up right now. We are out of time, but I would like to thank our wonderful panel of speakers who took time out from their busy schedule to be with us today.

Sheree Crute (57:32):

Please take a moment to share your feedback about our event by completing a brief survey that can be found at the bottom of the screen. In addition, I've seen many questions about the speaker's quotes, their data, their contact information, all of this will be available on our website. In addition, there will be a recording of the webinar that you will have access to, and you will also have access to our speaker slides. The webinar is also part of a NICHM series on the impact of race, inequity, and health, and you can access the previous webinars on our site.

Sheree Crute (58:15):

So again, please, don't forget to share your opinions on our survey, let us know. And again, thank you all so much for taking time out of your very busy day to join us.

Speaker Presentations

Addressing COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in Communities with Significant Health Disparities

George Mensah, MD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

A Legacy of Racism: Race-based Treatment in Healthcare

Lauren Powell, MPA, PhD

The Equitist

A Health Plan’s Role in Equitable Public Health

Dakasha Winton

BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee

A Health Plan’s Role in Equitable Public Health

Andrea Willis, MD

BlueCross BlueShield of Tennessee

More Related Content

See More on: Health Equity | Coronavirus