Webinar

Health During and After Incarceration

Time & Location

The unmet health needs of incarcerated people contribute to a public health crisis that disproportionately impacts Black and Brown men and women, and exacerbates existing health conditions for the almost 2 million Americans behind bars. These health challenges continue through reentry when more than 600,000 people return to the community each year. This reentry population experiences high rates of mental health issues, suicide, substance use disorders, disabilities, and physical disorders. Strengthening health care for incarcerated people and during reentry can reduce these disparities and recidivism.

In this webinar, leading health experts will address critical health issues current and formerly incarcerated people face and solutions to improving their health. Speakers discussed:

- The health care needs and challenges experienced by people during incarceration and reentry

- Medicaid reentry policies and a new care model for providing Medicaid-supported services to individuals both before and after release

- A clinic’s work to bridge the care gap between incarceration and reentry by ensuring continuity of care and social supports

0:04

Hello, everyone, and welcome to today's webinar, Health During and After Incarceration.

0:10

Before we begin, just a few tips to help you participate in today's event.

0:16

You have joined the webcast muted should you have any technical issues. During the webcast, please use the questions icon.

0:23

We'll also have the opportunity to submit text questions to the presenters, which you may submit at anytime throughout the event. We'll have time set aside at the end for live Q&A.

0:33

I would now like to introduce Kathryn and Santoro.

0:39

Good afternoon, I'm Catherine ..., Director of Programming at the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation. On behalf of ..., thank you for joining us today for this important discussion on critical health issues Facing Curran and formerly incarcerated people, and solutions to improving their house.

1:00

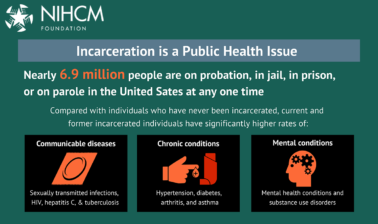

Incarceration exacerbates existing health conditions for the millions of Americans in prison and jail. Incarceration is a public health crisis that disproportionately impacts black and brown men and women.

1:14

Incarcerated people experience higher rates of communicable diseases, chronic conditions, and mental health conditions.

1:22

These health challenges continue when people return to their communities after incarceration.

1:28

This re-entry, population experiences high rates of mental health issues, suicide, substance use disorders, disabilities, and physical disorders, Strengthening health care for incarcerated people and during re-entry can reduce these disparities.

1:46

Today, we will hear from a prestigious panel of experts to learn more about health during and after incarceration, and discuss strategies to support individuals and improve their health.

1:59

Before we hear from them, I want to thank Nick ..., President and CEO, Nancy Chalk Lee, and the Nigam team, who helped to convene today's event.

2:08

You can find biographical information for our speakers, along with today's agenda and copies of their slides on our website.

2:16

We also invite you to join our conversation on Twitter using the hashtag re-entry House.

2:24

Am now pleased to introduce our first speaker, doctor Lauren Brinkley Rubinstein, Associate Professor and Director of the Re envisioning Health and Justice Lab in the Department of Population Health Sciences at Duke University. She is a national expert, and examining how the criminal legal system impacts people, families, and communities. We're so honored to have her with us today.

2:56

Thank you, Catherine, I appreciate the invitation, and I'm excited to spend the next 15 minutes or so, really setting the stage for other presenters.

3:08

OK, so, what I'm going to do is really talk about incarceration as a determinant of both individual and population health.

3:19

They're my credentials, again, I want to put forth a roadmap to give you a sense of what I'll discuss in the next few minutes. First, I'll talk about the history or context of incarceration in this country and be really explicit by what I mean when I talk about the criminal legal system or incarceration.

3:39

And then I'll go from there and speak about the intersection of incarceration and health.

3:47

So this is a chart that many of you may have seen before.

3:51

There are a couple of important things that I want to point out.

3:54

If we go all the way back to the beginning of this chart in the 18 eighties, even then the rate of incarceration in this country was far outpace that of other countries have always had this elevated rate of incarceration.

4:09

If we look to the seven to late seventies or early eighties, big changes in the number of people who are incarcerated in this country and that's largely due to the war on drugs, changes in sentencing, policies, harsher sentences. We look to the future if we look to now. This is a kind of dated chart, but the trends remain that incarceration in many ways.

4:32

The rate here has plateaued still much, much higher than the rate of incarceration in almost any other country.

4:43

And I want to be explicit about what I'm talking about when I talk about incarcerations.

4:48

There are state prisons, that account, for about one million people who are incarcerated. These are run by states. There's one in every single state. They tend to hold people who are sentenced and are serving longer sentences. Usually, about a year or longer. About 600,000 people in any given year are in local jails. Almost every county has one. Important things to remember about jails are that, one, they have a very short, average length of stay, about 72 hours, on average. So, people really churn in and out of jails.

5:24

If we look at any given year, about 11 million people in total, go in and out of our jail system. That's a massive number of people that are exposed to jail conditions. Smaller slice of the proportion is Federal systems, and we see Federal systems, and almost every state does, or people who are convicted of federal crimes, much smaller than state or local jails. Then, we have about four million people here on community supervision. So, under some type of cursor control, but in the community in this can be post release supervision or parole or probation.

6:02

And it's impossible to have this discussion without focusing in on racial inequities.

6:09

I'm using the phrase mass incarceration here. But, in fact, a lot of people really don't like that phrase, because it denotes that incarceration equally impacts all segments of society. And that's not true.

6:21

People prefer to use the phrase, hyper incarceration, because that more explicitly tells us that incarceration impacts certain communities more than others.

6:32

If we look at this graphic from the Prison Policy Initiative, we can see that black people, latin X people, and Native people, have greater proportion of people in prisons and jails as compared to the proportion of the general population. It's important to note that this doesn't have anything to do with crime. Law, if we take the example of drug use, lots and lots of studies have shown that, in fact, often white people use more drugs than there, these other groups.

7:03

It really is where police are at, where they're deployed, where resources are allocated, and it has to do with the legacies of slavery to Jim Crow, to mass incarceration, that has set up the current paradigm that creates racial inequities in the system itself.

7:23

I'm trained as a community psychologist. So, there are people on this call who work with me, who are really over the fact that I'm always having some kind of social ecological model on the screen. But here it is, again.

7:34

And I think this is a nice way for us to think about all the different levels of impacts that incarceration or other facets of the criminal legal system can have on people. If we start with individuals, we, that's easy, it's individual health behaviors that can be individual health outcomes.

7:51

I'll talk about those on the next slide, but I think it's important to also talk about the other levels that incarceration can impact. So, one is incarceration impacts families, relationships, friends, social networks, measures of social support.

8:08

It also impacts organizations, This is a little bit more of an abstract concept, but in my lab, we like to talk about this concept of carceral creep and it really is this creeping of carceral logic into other social institutions in society.

8:26

Couple of examples might be school systems that in more recent years have leaned into punitive solutions to address social problems. The presence of things like school resource officers.

8:39

It also we see it manifesting in healthcare.

8:43

So, the idea of the non compliant patient or Punitive nus when patients don't comply with doctor's orders there's also an emerging body of literature. That. Takes it beyond the individual. That looks at population health, and the impacts, or the relationship between community health outcomes and density of incarceration. I'll also talk about that on the next slide.

9:03

And lastly, I just want to talk a little bit about public policy, because the carceral system or the experience of incarceration can be quite different depending on where you might be incarcerated. And those of us that do this work often say you've been in one jail, you've been in one jail. It's true that cursor systems do have some similarities across systems, across facilities, but they're all really different. And the impacts of incarceration, the collateral consequences, or the restriction of rights that people might experience post release is really determined by local policy. And so, being incarcerated in one county could be very different to the next. And it can certainly be different from one state to the next.

9:48

And it certainly looks different now, depending, you know, compared to what it might have looked like several years ago. So it's also varying across time.

9:58

I want to spend the rest of my time really talking about disparities in health are the certain conditions that are over represented among people who are incarcerated. And, it's important to note that if we take any health outcome, we could probably map it on in the same way, because there are extreme disparities in almost every condition that you can think of when it comes to the incarcerated population.

10:25

On average, people who are incarcerated have at least two chronic conditions. So, an, a big over representation of chronic illness, in general in this population.

10:36

I'll focus in a little bit on some specific outcomes, though. So, first, thinking about infectious diseases.

10:42

Many studies have looked at the disproportionate rate of HIV, and has shown that it is 2 to 7 times higher. Additionally, about 17% of all people living with HIV in, the US. Pass through some carswell facility, in any given year.

11:00

If we take a look at Hepatitis C, we see similar disproportionality. The rate is about 8 to 21 times higher than the general population. And this goes on and on. With other sexually transmitted infections, we see similar patterns.

11:16

Not on this graphic is coven 19. This is an older graphic. Our group has done a lot of work, focusing in on disparities, relevant to testing, treatment, diagnosis, and mortality irrelevant took over 19.

11:32

We found that the rate of curve at 19 tends to be about five times higher than the general population, and the age adjusted death rate is about three times higher.

11:42

This links back to the, the over representation of chronic illness. So people who are incarcerated tended to suffer more severely from coven 19.

11:53

Also, on average, before the pandemic prisons were overcrowded. And so you have overcrowded facilities.

12:00

Very little ability to engage and things like social distancing, really created a perfect storm for transmission of covert 19 when it comes to substance use or mental health outcomes. We also see disparities here.

12:13

So if you see that bar chart here, big differences in the number or the rate, or the proportion of people who have substance use disorders, who are incarcerated facilities compared to the general population, and that is in part because illicit substance use can lead to incarceration. So there's, you know, it's hard to disentangle that.

12:35

We also see when it comes to serious mental illness and jails.

12:40

Big disproportionate rates, and I think many of us have heard that jails in this country have become the largest healthcare provider for mental health, and that is really because of gaps in access to mental health in the community itself. And we see this play out in prisons as well.

13:00

There's also an increased risk of mortality post release, and it runs the gamut of causes. So if we look at all cause mortality, disproportionate rates, if we look at specific things, there are some things that are important to note. So if we look at that immediate post release period, there's been a lot of work actually looking at the two week post release period. That has shown that. Overdose is a leading cause of death, And that really links back to this disproportionate rate of substance use disorders, among people who are incarcerated.

13:31

And then I want to focus just, finally, on community outcomes. So, I'm going to highlight two studies here because this takes us away from the individual and back to the population health perspectives. one recent study examined rates of sexually transmitted infections as a function of jail and prison incarceration rates.

13:50

They found that the documented differences and chlamydia and gonorrhea incidents between counties was partially attributable to those differences in jail and prison rates. So, we see this association between higher rates of incarceration, higher rates of various STIs.

14:07

Similarly, another study that was published in 20 21 found a strong association between jail incarceration and also, mortality from infectious diseases, chronic lower respiratory disease, drug use, and suicide.

14:23

So all of this is really to set the stage for the presentations that are coming up next.

14:28

And to give a little bit of insight into the impact of incarceration, how it can impact people, various health outcomes, impacts on families and also whole communities. And that's it for me, and I look forward to answering questions at the end of the presentation. Thank you.

14:46

Thank you so much for giving us the overview of the history of incarceration and the impact on health outcomes next. We will hear from Vicki, What Cino, executive, director of the Health and re-entry Project, an initiative to promote public health and public safety that she launched in February 2022 and partnership with the Council on Criminal Justice and Waxman Strategies.

15:12

Vicki is a principle, a viaduct consulting where she advises mission driven healthcare organizations to advance the health of people and communities. Vicki also served as deputy administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services from 20 15 to 20 17.

15:31

And, under her leadership at CMS, she oversaw the implementation of ACA expansions, Medicaid and Children's Health insurance program and groundbreaking policies to expand services for people with substance use disorders.

15:47

We're so grateful. She is with us today, to share her perspective and some new work.

15:56

Catherine, thanks so much. And thanks to the ... Foundation for highlighting this critical, but sometimes under recognized topic, It's very valuable to be with you all here today.

16:13

I'm having a slight problem advancing my slides. Let me try that again.

16:18

Here we go. Now we're in business.

16:21

So you've heard already from doctor Brinkley Rubinstein a bit about the impact of incarceration on people's health. What I'd like to cut to cover with you today is building on that, talking about the challenges that the health system faces in meeting the needs of people who've experienced incarceration.

16:43

And then talking about some of the very promising policy changes that are under active discussion now to start changing medicaid's role to better meet the needs of people as they're leaving. And I'd also like to share with you the work of My Health and re-entry Project. And specifically the roadmap that harp created with stakeholder input that's designed to lay the groundwork for a vision of implementing these new Medicaid policy changes. In a way that advances the health and well-being of people, leaving incarceration and engages people across the health and criminal justice sectors. as well as people with direct experience of incarceration and paving The way to these new changes. As I go through each of my slides, I'll pull out a few key pieces of information and leave the rest to you to absorb over the course of the conversation. I'd be happy to answer questions about them at the end.

17:51

So as you saw from Laurens slide that had the doubles, I was the different concentric circles. There are many ways of thinking about the impact of incarceration in the criminal justice system. Today with this audience, I wanted to talk about the impact that incarceration, and the way in which we respond to it as health system leaders is affecting the health system. Specifically, you've heard about the elevated rates of death, including deaths from opioid overdoses, the high rates of public health issues, the high rates of physical and chronic conditions in prisons and jails.

18:32

And when you think about that, from a health system perspective, and how and the community health system that serves people before they're incarcerated and after incarcerated, It's clear that are, the way in which we're responding to the health needs of people, as they re enter, is not sufficiently moving the needle, and it's also how holding the health system back from some commonly shared goals. So, those health system leaders, we think about, How do we increase life expectancy? How do we improve public health? How do we advance equity?

19:07

How do we address national crises of mental health and substance use disorder, and how do we avoid use unnecessary use of high cost settings, like emergency rooms? All of those goals are challenged by the data that you see on the slide and that you saw from Lauren a few minutes ago.

19:27

As you've heard, many millions of people experience either prison or jail each year, and as you've also heard, many of them are disproportionately black and people of color.

19:38

In addition, incarceration is highly correlated with poverty.

19:43

So, I invite you to consider that the population that's entering prison and jail is disproportionately of color and disproportionately poor.

19:51

As you've heard, people who are incarcerated have higher rates of physical health conditions, including both chronic and infectious diseases, and very high rates of mental health and substance use disorders.

20:04

Yet it released, although some people successfully re-integrate in the community into the community. We see very high death rates from a multitude of causes but particularly opioid overdose deaths.

20:15

And you've also already heard about some of the impact that release strategies are having on families and communities, and they're also holding back some key public safety goals.

20:28

But we may be at a turning point, in terms of policy, and specifically developing a re-entry policy that can better meet the needs of people as they leave incarceration.

20:40

Historically, there has been no systematic approach to meeting people's needs at re-entry. If you were to Canvas the re-entry landscape, you would see that there are a few bright spots, but no far reaching approach.

20:54

And as you've already heard, most correctional health services are financed at the state and local level. Most services are provided at those levels, and they're provided independent of the community health care system.

21:10

As as many health leaders and criminal justice leaders have thought about how to start building towards a stronger approach, it has been natural to turn towards Medicaid, Because Medicaid, as the dominant ensure of the low-income population in the United States, has significant reach into the population of people who've experienced the justice system.

21:36

Medicaid like private insurance and Medicare, has historically played very little role, and provide and financing correctional health care services.

21:48

Medicaid has been prohibited from paying for everything except for community hospital stays, since it was created in 19 65, and over the past several years. And, in particular. Since the coverage expansions of the Affordable Care Act have translated into record numbers of people in the United States having access to affordable health coverage. Some States and local governments have made progress connecting people to Medicaid services after they were released.

22:17

And now we have a cadre of policymakers who are interested in creating greater continuity of services for people as they're released, by allowing Medicaid to start, for the first time, covering some services before people leave prison and jail.

22:34

And the idea is that by doing that, Medicaid can provide a bridge to community health care services when people are released and better meet the multitude of health needs, that people who've experienced incarceration experience.

22:52

These changes could take place, either nationally, through Congress, or on a state specific basis, through administrative action by the administration. And I'll spend just a moment on each. The federal legislative pathway, there have been a few different types of proposals to change Medicaid role at re-entry.

23:10

The one that has advanced the furthest is the Medicaid re-entry Act, which was introduced on a bipartisan basis, in both houses, and would require Medicaid across the country to cover services and the 30 days prior to release. It's passed the House three times and is currently in the Senate, and remains in the mix for a potential year end legislative package.

23:36

In the meantime, not Waiting for Congress, all 11 states have approached the Biden Administration with proposals to allow Medicaid to cover in their states, services at re-entry prior to release.

23:52

11 states so far have submitted re-entry, waiver proposals to CMS waivers, or tools that has long existed in the Medicaid program to pilot new approaches. And although the specifics of the waivers, very, they tend to focus on providing a subset of high needs, people who are leaving the justice system, with a subset of services, Generally, they focus on services like care management, connecting people to medication. But in a few cases, states have proposed to provide more comprehensive benefits in the period prior to release.

24:33

So, recognizing that there has been over the past 2 to 3 years, renewed interest, and even policy momentum around the idea of changing medicaid's role or re-entry, I was lucky to partner with the Council on Criminal Justice and Waxman Strategies to create earlier this year as a health and re-entry project project. And the goal of that project is really to identify if we're going to, to allow Medicaid to start covering the services, how do we break this, this ground?

25:06

We pull this project together in recognition that to really successfully implement the changes, we needed input from health system leaders, from criminal justice leaders, some social justice leaders, and from people who've experienced direct incarceration.

25:22

Over the course of the year, we've engaged more than 70 stakeholders in these conversations, and our work has been guided by a fantastic advisory committee of cross sector leaders whose engagement and interest has been critical as we've as we've moved to these issues forward.

25:41

Our synthesis of stakeholder feedback was released in July and is called redesigning re-entry.

25:48

I want to highlight three major elements of rigid redesigning re-entry, and I'll spend a minute on each of them.

25:55

In my remaining time, we established guiding principles, high level principles for how we can execute these changes in such a way that makes it maximum impact for people who've experienced incarceration. We identified the outlines of a new care model that can support people re entering.

26:14

And finally, we identified seven essential actions for policymakers who are mate who are changing policy and implementing new policies to consider.

26:28

Our guiding principle, those focus on strengthening continuity of care, but not just that. it's doing it in such a way that there's an explicit goal of helping people after incarceration return to their families and communities healthy and whole.

26:44

Those words healthy and whole were North Star established by one of our advisory committee members. Topeka Sam, Ladies had Hope ministries. And, as soon as she said it, it got immediate reaction from our stakeholders as a fantastic North Star.

27:01

Some of the keys to helping people return to communities healthy and whole is advancing access to evidence based clinical services at re-entry, but also, and our stakeholders were very clear about this, thinking about the larger array of community services that needs to be in place.

27:19

But too often isn't, That can help people have their health and behavioral health needs met before they ever experienced incarceration and ideally would help them, avoid incarceration, and then also making sure those community services are available and re-entry.

27:38

The care model we outline is focused on primary care, but primary care, with a strong connection and integration to behavioral health services, a clear focus on active patient engagement, degree of navigation. So, helping an individual navigate a system, because, historically, people leaving incarceration has been left to navigate systems on their own. In many cases, people will need trauma informed approaches. And, of course, recognizing that health is not the only need that someone has incarcerate when they leave incarceration, helping people access both, health, and social supports.

28:21

And, finally, as I said, we identified some key actions for policymakers, And I'll highlight just a few of them here. Aligning healthcare services that Medicaid is going to cover with the standards that pertain in the community, and doing that requires an investment in systems and infrastructure. There's very little infrastructure in place in most places in the country to share information and data about a person before and after they're released. And those types of investments will be foundational.

28:55

And then, finally, cross sector collaboration.

28:58

It was clear, although we had a very group, strong group of committed leaders, who joined us in our stakeholder engagement, that that was really just the beginning.

29:08

And the house and the criminal justice systems need to foster greater understanding of each other's speak, the same language, and develop common goals for advancing the health of people who have experienced incarceration, And that, along with that housing, community providers, social providers, and perhaps most critically, people who have direct experience of incarceration, should all be at the table to navigate and implement these changes.

29:42

I'd like to end by thanking our my partners, the 70 stakeholders who engaged with us so actively. And my, for philanthropic partners, The RX Foundation, California Health Care Foundation, Commonwealth Fund Fund and Schuster, ... Family Foundation, and I'll end by saying the re-entry work of heart is not done.

30:05

We want to make this re-entry Roadmap a reality. And if and when these policy changes are made by the Federal Government and states, we would welcome and look forward to the input of the people on this webinar today on how we can help carry those changes out in partnership with you.

30:25

There are resources available to get more detail on any of this, And thank you, all, and thank you, Catherine. I'll turn it right back to you.

30:36

Thank you so much for highlighting the importance of Medicaid for the re-entry population, and for sharing your work on the heart project. Our final speaker will be doctor Divya Van Cat.

30:51

She is the Inclusion, Health Track Director, Rethinking, Incarceration, and Empowering Recovery Clinic, and the Allegheny Health Network at the Post Incarceration Clinic. Doctor Van Cat works on transitioning patients out of incarceration while focusing on their health and social determinants of health. She's also the medical director of the Prevention Point, Pittsburgh Mobile Medical Unit, and her work focuses on the integration of harm reduction and low barrier access into healthcare settings, and we are so happy to have her with us today. Doctor Venkatesh.

31:30

Alright, I think I have control of the screen. It's so nice to talk to you all today.

31:35

I'll be building on what my previous presenter book about, which is really the idea of creating a model that helped people re enter into society after incarceration.

31:46

So I'll be talking about our model called the Rethinking Incarceration and Empowering Recovery Clinic, or the River Clinic for short.

31:55

So my objective today are number one, to describe a post incarceration care model to, to outline the ...

32:02

River Clinic and three to demonstrate the impact of our model.

32:08

So just like everyone has kind of talked about already, why is a post incarceration care model important?

32:14

When we build these types of models, it's important to acknowledge three things. one is that there is a gap that exists between impartial settings and civilian life.

32:22

two is that we need to create an infrastructure that ensures the continuity of care between complex setting, partial settings, and outside of these personal settings.

32:33

And lastly, to provide support to address the social determinants of incarceration.

32:37

Like my previous presenters have mentioned, incarceration is so much more than health care.

32:42

It often involves things like access to education, access to a job, housing, health care, insurance, really just going back to a previous environment where someone may have been incarcerated.

32:57

What is a post incarceration care model? And many of these model patients are referred directly from Carceral setting to a post incarceration clinic.

33:05

Typically, prior medical records are shared between the cursor setting and the clinic in a HIPAA compliant method.

33:12

Post incarceration care then focuses on acute and chronic medical problems, connectivity within society in collaboration with local organizations to improve health and wellness outcomes.

33:25

This is just a typical flow that might happen within a post incarceration care model. So someone is released from incarceration and through a direct referral to the clinic contact with the clinic is made.

33:36

Many of these clinics have access to behavioral health clinicians, a social worker, healthcare provider, community health workers, and nurse navigators.

33:47

I want to highlight one post incarceration care model that has really done an excellent job demonstrating their success and the importance of this model.

33:55

This is called a Transition's Clinic.

33:58

They were started, I believe, out of, and UCSF, and are at Yale, and many other places.

34:03

But what I really like about this diagram is kind of what all of our missions are, is number one is we need to build capacity for team based, patient centered care.

34:12

In all of these models, the most important thing is that we're putting our patient, or our client right at the center of our services.

34:19

It's crucial to hire and integrate community health workers into these models.

34:23

People who have had a history of incarceration or even understand the neighborhoods from which our patients are coming from.

34:30

We need to leverage systems and services that exist within the health care system that we exist in.

34:36

Community partners are critical to making sure that our patients can navigate through health care and life after incarceration.

34:45

Their model success, what they've seen as multiple things. Some of the important things that I think really count towards our clinic are highlighted here.

34:53

one is that in the Transition Clinic out of San Francisco, there were people who are less likely to visit the Emergency Department and had 50% fewer emergency department visits.

35:05

This is a really, really awesome bargaining chip within a health care system because it decreases ER utilization and health care spending.

35:12

$912 were spent less per year in healthcare cost utilization.

35:17

More than half of the participants had at least two primary care visits after release engagement within the program.

35:24

Additionally, this model reduced illicit drug use and overdose risk, criminal behavior, recidivism, and most importantly, mortality.

35:32

Again, these models exist, not just to help improve someone's life after incarceration, but to help our clients live, which has been really highlighted during the pandemic.

35:44

So now we'll talk a little bit about what the CH River Clinic is all about.

35:48

These are keys to success. So, the ...

35:50

River Clinic is a part of Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

35:55

We're also part of a greater organization called the Center for Inclusion Health, which really focuses on traditionally excluded populations.

36:03

So these are three feeder system, has been part of it, the ecosystem that we exist in.

36:08

So the Center for Inclusion Health, it's extremely embedded within the community organizations in Pittsburgh, because of that. It was pretty, it helped us a lot, get in touch with other organizations and really find support within our community.

36:21

Additionally, our health network has a contract with the Alleghany County Jail.

36:26

We provide some of the healthcare providers within the jail.

36:28

When we wanted to make this clinic, it was extremely important, and we got the Alleghany County jail on board with that.

36:34

This often meant multiple phone calls per week, e-mails, trying to figure out exactly how we could get a referral system in process and support the Allegheny County jail, especially during the ... 19 pandemic.

36:48

Again, like I highlighted, one of the more important parts of our clinic is our community based model.

36:53

We really believe in outreach within the community, and engaging the people around us to ensure the success of our clients.

37:01

We also really care about a warm handoff.

37:03

So, like I mentioned, the health care providers within the jail also are a part of Allegheny Health Network.

37:09

We've worked with Alleghany County Jail to ensure a HIPAA compliant process in order to get patient referral.

37:15

When patients are in the jail, and when they come out of the jail, we ensure that patients have given us, like, a written consent, so we can talk about their healthcare amongst providers.

37:26

What are our clinic goals, and why did we created?

37:29

What we really cared about is that all these patients would come out of the jail and had no access to health care. There's nowhere for people to go to get almost like a warm security blanket around them or a safety net when they were trying to re-integrate into society.

37:43

So, one of our first goals was to increase access to health insurance and social services.

37:48

We care about providing comprehensive care to recently incarcerated individuals will face multiple social determinants health issues.

37:56

We also treat a variety of health care conditions, including diabetes, substance use disorders, hepatitis C, and behavioral health.

38:03

Our goal is to alleviate the social determinant of health by engaging with an in clinic social worker and a community health worker.

38:11

And our long term goal is to transition patients to long term primary care providers after engagement within our clinic.

38:20

This is a really busy slide, but it's just to show you the flow of how our clinic model works.

38:25

So, the Discharge and Release Team at the jail will actually notify us when a patient is about to be released or has already been released.

38:32

Our social worker and community health workers will then contact the patient within 24 hours of release.

38:38

This is really critical, as many of the previous presentations highlighted the data around post incarceration care, within those first two weeks, is really, when our patients are at highest risk for overdose.

38:49

Being in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Opioids have really hit our community, and so it's really important that we engage with patients right away and provide low barrier care.

38:59

Once our social worker or community health worker has been able to connect with the patient, they get an immediate connection to a health care provider.

39:08

And during that time, we often provide we often prescribe medication for opioid use disorder.

39:13

Prior to coming to the appointment, there are multiple touch points, but a team member.

39:17

Our team is on it, they're constantly calling patients, texting them, trying to figure out exactly what they need in order to be successful in their lives.

39:25

The patient then arrived to her appointment.

39:28

During this time, a healthcare provider will complete their initial appointment assessment for things like chronic conditions and medication.

39:34

But frankly, I think most of our patients come, because of the rest of our team.

39:38

The social worker and community health workers really work towards helping patients we integrate.

39:43

They'll do things like social determines of health screening needs, will ensure that people are transportation. We work pretty intensely with our criminal justice system to advocate for patients to stay out of incarceration.

39:59

So this is our clinic structure.

40:01

We have two physician, a nurse practitioner, and a pharmacist.

40:04

And together, we address things like medications for opioid use disorder, hepatitis C, and really just a low barrier model of care.

40:12

Our nurse navigator focuses on medical management within the clinic.

40:16

Our community health worker visit people actually within ACG so that she can start at that establishing a rapport with patient immediately.

40:23

Oftentimes, exiting incarceration can eat quite complicated, really just difficult. And so by having someone who has already seen someone within the Alleghany County jail, still, a person is often more likely to reach out to us because they know that warm faith.

40:40

She also works very closely with community based organizations to ensure the optimal community engagement on release.

40:46

Our social worker works very closely with drug and alcohol programs to ensure that patient outcomes have been improved with substance use disorders.

40:54

She also worked collaboratively with housing team to improve access to safety, and often provide things like brief intervention for our patients.

41:02

Our patient care navigator ensures quick access to health insurance and benefits on release.

41:06

Most of our patients, their Medicaid product, has been turned off or has been, as they say, I guess I put on hold on release. But our patients don't have a way of actually signing up for health care again, to ensure that that is turned on quickly.

41:21

And she works very closely with our health insurance, is around here to do that.

41:25

She also establishes continuity of care plans for our patients after they've completed time with us at the River Clinic.

41:30

We also, the psychiatrists have been funded by a grant.

41:33

And she focuses on the effective effective access to care by regular screenings and things like the PHQ nine and PTSD screening.

41:43

What I really wanted to highlight, though, is we're much more than a clinic. Our whole clinic model is really based on this concept of outreach.

41:50

Most of the week, our team is actually not even in a clinical setting, one day per week, to have to use, actually, the team is parked, literally outside of the jail, and we're just welcoming people who've been released from jail.

42:02

We do a number of things. We help people get bus tickets. At that point, we see if people have medication needs, we help people get into shelters that are available throughout the city.

42:11

We also park in different parts of the city to see if we can find people who just need help. Most recently, we parked at a soup kitchen where a lot of our patients and clients actually go to, and we just reach out to try to find them.

42:24

one of our biggest barriers is, actually, most of our clients don't have a cell phone.

42:28

And so that requires a lot of innovative thinking.

42:30

And we've done that by really going into the community and immersing ourselves and what our patients may be experiencing.

42:37

When we hired our people in our clinic, we ensured that we hired people who are from the neighborhoods that we were serving.

42:43

And that has really served us because our the people that are working with us, know our patients the best and actually can guide how we're designing the clinic every step of the way.

42:53

We also go within Allegheny County jail.

42:55

We have our community health worker and our social worker physically go inside the jail, meet patients regularly, being that it is a jail. A lot of our patients do end up being re incarcerated. And so having our community health worker in our social worker go back in, helps patients realize that we're always there for them.

43:14

So the outcomes that we always have looked at are things like reducing hospitalizations, treating and eradicating Hepatitis B, reducing opioid overdoses and increasing retention in medication for Opioid Use Disorder.

43:26

Ultimately, we'd like to reduce recidivism and also show reduction in the social determinants of health needs.

43:33

We started our clinic in June of 2021, and we've had over 400 referrals from Allegheny County jail.

43:39

We've actually engaged with 60% or more of those referrals, either by a phone call or finding them within the community.

43:46

In this moment, we have 50 active patients.

43:49

Over 100 people have completed care with us and transitioned into their community.

43:54

This means that we've made a warm handoff to a primary care physician, a treatment provider of any sort, or even just other case, management services.

44:04

We've actually returned reduced rates of return to use, and reduce rates of recidivism.

44:08

By engaging patients and rehabilitative programs, we advocate within a lot of the court system to have patients, instead of going back to actually go into treatment, and they work with patients while they're in treatment, to make sure that they stay engaged.

44:22

12 patients have completed treatment for hepatitis C, and achieve the FPR through these patients have been actively using, and sometimes don't even come to clinical. We figure out a way to get them their medication.

44:32

And of the patients that we've engaged with, only one has an overdose within two weeks of being released from jail.

44:38

This is a drastic decrease in the numbers that we know exist.

44:43

That's all that I have about our clinic.

44:45

I'm looking forward to answering any of your questions.

44:48

But if you have any questions outside of that, this is my e-mail address. Feel free to e-mail me.

44:55

Thank you so much, doctor Van Cat, for sharing the work of the river clinic and your care model. We'd like to use the remaining time for Q&A with our audience. Please continue to submit your questions.

45:08

I'll invite our panelists to come back on video and come off mute.

45:15

So, a first question, we had, a lot of comments people are so interested in learning about, and the Clinic and Pittsburgh, as well as some of the project's potential projects that Vicki mentioned with some Medicaid waivers.

45:35

Can you talk a little bit about, me, know, the range of post incarceration models and services that are existing across the country And sort of how can this, how can this change?

45:49

So people can receive necessary service says maybe doctor Von ..., you could talk a little bit more about how you were able to get it, know off the ground and what that meant in terms of collaboration.

46:01

And then Vikki maybe a little bit about, you know, some of the potential Medicaid and waiver projects.

46:09

Sure, I'm, the only person ever actually had heard about this type of model with when I went to a conference.

46:16

And I had heard doctor Emily Wain talk about there, our clinic, the Transitions Health Network.

46:23

And I was really fascinated by this idea of, how do we get people out of incarceration but actually continue their care. So, there's many types of models that exist.

46:32

Our model is really centered on community engagement.

46:36

What I've seen, I do a lot of addiction medicine, A lot of our patients are entering communities where it's so tough to go back.

46:44

There often entering the same, the same neighborhood, the same house that they were first incarcerated in. And that can be really traumatizing for a lot of our patients.

46:52

On top of that, it is really difficult to kind of stay out of jail when those may be neighborhood where there are more police officers or you do have existing warrant.

47:02

So we work really hard with the community partners that we've made to try to figure out ways that we can reduce the type of recidivism and make it a little bit less difficult for our patients to go back.

47:14

That has really just been an effort by our community health workers.

47:19

We really care about elevating the voices of people who had existed in these communities before and will exist after us, frankly. Our community health workers actually go to the neighborhood and find different community organizations that we should be partnering with.

47:32

They literally park next to a patient's houses and ask, Where can I? Where would you go if you needed help today?

47:37

And I think that's really been a key success for us.

47:41

We also work within a health Network, and we try really hard to advocate for our Patients health network. We work with high mark.

47:48

We work with a lot of funders close, close to us, and we make sure that their voices are heard. We work to try to get Medicaid turned on as quickly as possible, and one of our community health workers always said that she's going to go to their senators and let them know that Medicaid should always be on and not something that has turned off during incarceration. Not sure how possible that is.

48:10

Those are the people that we've hired.

48:15

Um, thanks so much, doctor ..., first starting with that. There's so much about your model that I think is promising and that people could really learn from. Katherine, with respect to the Medicaid policy changes that are under consideration through waivers, call a couple of things out. First, if you were to look across the 11 states at what's being proposed, most states are focusing on, how do we reach people in that time period, Which could range from 30 to 90 days, depending on the state's proposal, to start engaging with them, to prepare them for a release?

48:55

That could look something like the model that doctor Van Cat describes, if community health workers going into facilities, I know in California, which is one of the states that are proposed to, waivers are looking at having an interaction with an enhanced case manager that that gets to know the beneficiary on their health needs prior to release. And, I would say the across the 11 states, that the tendency is to that model. In case of case management, how do you connect someone to medications, including medications for opioid use disorder?

49:31

So that they're leaving the prison or jail with medications, in hand, wherever, whenever possible, But those, that's speaking to the average across the states, there are exceptions.

49:43

Both Vermont and Utah have proposed to go far beyond that by having Medicaid covered all of the same services that are covered for people who live in the community.

49:56

And Kentucky, had their waiver focuses specifically on substance use disorder. There's a history of Kentucky of close collaboration between their health and criminal justice sectors. And I think that their waiver proposal really reflects a shared commitment across sectors to trying to leverage Medicaid in a correctional environment to move the needle on opioid use disorder. And the other thing I will say, although there's these state specific proposals, CMS, which is the Federal agency that will, that will negotiate and approve these papers, and I think those conversations are are are underway, right now, is also required by Congress to issue waiver guidance for all States.

50:40

That was a requirement that Congress imposed in the Support Act of 2018.

50:45

And I think having these 11 states make proposals to CMS really gives sam as a nice range of approaches to consider as they write national policy. And so, all states will be able to look to that national policy when it's released for what it is that the Federal government is interested in supporting through Medicaid.

51:12

If I could take just one more minute, Delia History has mentioned twice this issue of connecting people to Medicaid eligibility. As they're released. And I will say that you do not need a waiver for that. That could be done now.

51:26

And the issues there are really operational and systems issues, But if But there are models for how to do that, Ohio, for example, has created a specific eligibility unit, so that people who are leaving incarceration can connect to that unit and try to get their Medicaid coverage, turned on quickly. Ohio also use peer supports in their prison system that starts to interact with beneficiaries well, before release, to talk about health coverage, and what it can mean in terms of access to services. Also, New Mexico, Some places in New Mexico. I've done a really strong job of connecting People to coverage. They've had some application assisters working in the prisons and jails to help people enroll in Medicaid coverage and to try to keep it as active as possible on release. So, it's a work in progress in many places, but there are some real bright spots in terms of making coverage as continuous as possible for people.

52:30

Great. We had several questions about community health workers, and if there's specific trainings, are they part of a broader network?

52:41

And then, also, more here?

52:48

I guess if, if communities have a community health worker network in place, how can they best can act with a program like this in their community?

53:03

So, the Community Health Worker Model is not, it's not new.

53:07

You know, it's like existed in countries for long before America adopted it.

53:13

In Pennsylvania, we do have a Community health work network worker network, where they actually do undergo formal training. Which, I think is really awesome for our community health workers.

53:25

Both of them, I think one of them did not complete college. one of them did complete college. But, the fact that we were able to give them just like extra title, and this extra certification to highlight their lived experience has been really awesome for them, and they're very excited about it.

53:38

So when we were hiring, boatman had found other jobs, I think, within the Health Network, but we did hire another peer that came from the community. And usually, I think the best way to go about it is to actually ask people within the community themselves. A lot of our patients are actually really interested in doing community health worker work after we can figure out what's going on with incarceration and with their legal Whoa, there are at this point. But it's really, I think, important to actually hire within the community. A lot of communities, they may not have. like an actual network that we would think that it's like a job posting, right?

54:12

But I think if you go to a lot of the big community centers to find people, I think really common places there, please, Like YMCAs are really great place to kind of meet people and try to figure out, like, Who are the leaders in their community and what what do they want to say?

54:26

We have a lot of churches around here where there are a lot of people who are interested in things like Community Health Worker Model.

54:33

Again, I can't, I cannot highlight more how important it is to have community health workers, because I think that's how we're really able to deliver effective care.

54:41

I don't think my, my knowledge at any community is even close to what people who have lived experience have and how we are able to navigate things so effectively.

54:53

Thank you.

54:56

We had a few questions about access to maternal health care during, you know, pregnant and post-partum period during incarceration and also just access to screening services.

55:12

Are there any examples, or, you know, strategies you could share for people that are interested and expanding work in that area?

55:25

I don't know, Lauren, if you know any research on.

55:29

Yeah, it's a great question.

55:32

These questions come up a lot, and that the answer is often not very satisfactory, because every place is very different and every system is really different. So when it comes to screenings, there are some places that have really robust screening in place, lots of resources that might be devoted to things like preventative care. And then in other places, just absolutely no resources at all.

56:00

So you see, there are, you know, I would say it's probably more standard to have screenings for things like HIV. And then usually the medical intake process is it can happen in two steps. So, right, when you come in, someone might ask, do you have any conditions? Are you taking any medications?

56:19

Then, you know, two weeks to a month down the road, you might have a more formal assessment by a healthcare provider that's doing more in-depth screening, or asking about conditions that might exist. Again, that looks really different across different systems. And when it comes to maternal health, I think, in some ways, that's a very similar answer, exists. I think the community standard of care is often minimally met, at least in carceral facilities. But there's actually a lot of opacity around how those things operationalized, or very little measurement around how it actually works.

56:59

Thank you.

57:01

Katherine, if I could just say, welcome.

57:04

This question is, even though I cannot point to, to a lot of specific models, I think, you know, someone who's concerned with health policy, I've seen so much momentum and energy over the past two years around maternal health, an infant focus on new moms and in particular black moms.

57:25

But when I haven't seen follow on that, is the recognition that the role of the, about the role that incarceration is client for those new moms and how challenging it is to be pregnant or to give birth in a carceral facility and the impact that that has on the health of the Mom, the ability of the Mom and the infant to attach and on the mental health and well-being of books. So I will say, I challenge to the fields of people who've gathered here today, is as we think about Medicaid and re-entry. We should also think about new Medicaid policies, which more than half of states have taken up to keep Medicaid post-partum coverage active for a year. And the intersection between those two and how we can really identify ways that for these low income moms who have experienced incarceration, recognize that there's a real opportunity here to better meet their needs and the needs of their children and families.

58:28

Thank you.

58:31

We are almost out of time, and there's so many great questions. So, we will try to share these with our speakers, if they're able to take some of them.

58:42

For maybe a wrap up question. If you could just share, you know, offer us a final thought on, you know, what do you feel as, you know, the greatest barrier but also kind of maybe low hanging fruit or advice for next steps that folks in our audience can consider for advancing work on this topic?

59:07

I'm happy to go first and just say that I think often there's a real siloing of resources and also consideration of the health of people who are incarcerated.

59:20

We saw we saw, especially in the context of the cupboard 19 pandemic that a lot of public health, Department of State or local level, really didn't have relationships with their local jails and prisons.

59:32

And so, something that I like to say all the time is that there really needs to be better collaboration and better partnership between different public health entities and in jails and prisons, and at the local and the state and the federal level.

59:48

Thank you.

59:50

I totally agree with that. And, additionally, you know, it's very hard to build those relationships during a crisis.

59:58

And so I think, and hope that one thing that we can accomplish in this time period, where we're looking at these issues more closely as a health system than we have before, is, like, can we build partnerships that indoor, and that are there, when we want to address Hep C that are there, we knew how to address that, are there when we need to, to address the opioid overdose epidemic. So desperate plus, Y, into, to, Lauren's comments. And the last thing I'll say is, I just wanted to pull three things that doctor Van Cat said out from her presentation is, things where I think people can learn from nationally. one, is the ability to access data.

1:00:38

And access information, Alleghany County is really unique, and it's integrated data system and investments in those types of systems really underpin care delivery and gives us the ability to see what's happening prior to release and after release. The second is the degree of outreach in the community that doctor Van Cat described. And along with that, the third is the emphasis on people from the community. I really think that a community health focus is the key to success here.

1:01:13

It's something that's not always the larger US health systems, greatest strengths, but if we're really going to think about moving the needle on a population that has significant needs and has experienced significant disadvantage, I think that community health focus is, is worth considering.

1:01:36

I echo what everyone said. I think one of the major things that we talked about in this, which, you know, kind of mentioned, is Medicaid, and I think just how it's standardized across the country. one thing that we struggle with consistently is that for some reason only behavioral health is turned on immediately after relief and medical. Which is a huge issue for us because we are prescribing medications for things like opioid use disorder, but.

1:02:01

It sounds like some states are really doing a great job at that, and so I wish that every, I wish there was a way for us to standardize how that's done in every State.

1:02:09

So that way, this population wouldn't be at the mercy of when a state would want to turn something on or how it's turned on.

1:02:16

I think the last thing is, I think, I'm guessing there's a variety of people on this call.

1:02:21

But, I think just recognizing that, this population is not, you know, I think one day I hear from my patients allotted that there are described as criminals, right?

1:02:29

There described as people who are undeserving. There's a lot of guilt that goes into whatever has happened.

1:02:34

And I think that we need to remember that, everyone who everyone that we see, is a person, right?

1:02:40

And everyone has different life circumstances that have led to where they are today? I don't know, I would be to different places. My life had been different. And not just And I got lucky, right?

1:02:49

And I think that remembering that everyone that we interface with, had story, they have struggles, and that our job is, really listen to them, just because someone comes in and they have a, quote, unquote, record, or they have, they've had some life circumstances led him to be where they are. That doesn't mean that we should care for them. And I think that's really low. Hanging.

1:03:05

Fruit is treating each other kindly and with respect and knowing that we all come from difficult backgrounds, sometimes our job in healthcare is to make it better for everyone.

1:03:16

Thank you for that. And thank you all for the work that you're doing to advance this, addressing this topic. And thank you for being with us and sharing your perspectives. Thank you to our audience for joining the discussion and all of your great questions. Your feedback is important to us, Please take a moment to complete a brief survey on your screen. The slides are available on our website, and we'll also be making a recording.

1:03:46

I'm just available, so we hope that you can check that out, as well as some of ... additional resources, and some resources from the speakers, as well on our website. So, thank you all so much for joining us today!

1:04:02

Thank you!

1:04:05

Thank you.

Lauren Brinkley-Rubinstein, PhD

Associate Professor at Duke University

Vikki Wachino

Executive Director of the Health and Reentry Project, Principal of Viaduct Consulting LLC, Former Deputy Administrator and Director, Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services, CMS

Divya Venkat, MD

Inclusion Health Track Director, Rethinking Incarceration and Empowering Recovery’ (RIvER) Clinic, Center for Inclusion Health, Allegheny Health Network

Health and Reentry Project, Issue Brief 1: Medicaid and Reentry Policy Changes and Considerations for Improving Public Health and Public Safety, March 23, 2022.

Health and Reentry Project Issue Brief 2: Redesigning Reentry: How Medicaid Can Improve Health and Safety by Smoothing Transitions from Incarceration to Community, July 14, 2022.

Providing Health Care at Reentry Is a Critical Step in Criminal Justice Reform, The Commonwealth Fund, Blog, September 9, 2022.

More Related Content

See More on: Health Equity | Social Determinants of Health