Webinar

Systemic Racism & Health: Solutions, Making Change Happen

Time & Location

The COVID-19 pandemic has placed a spotlight on the impact of systemic racism on the health of Black Americans. Long-standing social and economic inequities have contributed to multiple social determinants of health that increase the risk of getting or dying from COVID-19. In the United States, Black Americans are dying at 2.5 times the rate of white Americans, while facing barriers to testing, treatment, and options for prevention and self-protection. This webinar discussed how systemic racism harms health, and how solutions-based approaches at the state and community level are making a difference.

The first part in our Stopping the Other Pandemic: Systemic Racism and Health series, this webinar explored the impact of systemic racism on the health of Black Americans. Speakers discussed:

- How health is not created in the health system and how we need to sustain a focus on racism moving forward and improving health and the health care system

- A health plan’s comprehensive approach to addressing racism in health care through provider anti-bias training, efforts to increase workforce diversity and the incorporation of equity into value-based care arrangements

- How a local system of health centers is focusing on grassroots strategies and efforts to address systemic racism and improve health outcomes in the community

Sheree Crute (00:00): Good afternoon everyone. Thank you for joining us. I'm Sheree Crute, director of communications at the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, NIHCM. On behalf of NIHCM Foundation, thank you all for joining us today to explore this important topic at such a critical time in our history. Our goal today is to offer information on understanding the impact of systemic racism on the health and wellbeing of black Americans, as well as some of the ways that affects us as a society before looking at actionable path to positive change. This webinar's the first in the NIHCM series exploring the links between systemic racism and health inequity among black, LatinX and other communities of color in the United States.

Sheree Crute (00:48): Well, systemic racism has always contributed to health disparities in America. The realization that black Americans are dying at 2.5 times the rate of white Americans from COVID-19 when we are only 13% of the population, when we only 13% of the population, places a spotlight on the devastating impact inequality and discrimination can have on health.

Sheree Crute (01:20): While some of the risks that contribute to high mortality and COVID-19 rates among black Americans, such as poor access to quality, culturally competent health care, dangerous frontline worker jobs, food and housing insecurity maybe familiar to many of us, today, we will focus on how we got here and effective ways that people working at the community, state and health industry level, as well as policy makers can bring about positive change in the communities they serve.

Sheree Crute (01:55): To discuss the systemic racism and public health crisis, as well as strategies and best practices to address it, we are pleased to have a prestigious panel of experts with us today. Before we hear from them, I want to thank NIHCM's president and CEO, Nancy Chockley and the NIHCM team who helped convene and curate today's events. In addition, you can find biographical information for all of our speakers, along with today's agenda and copies of their slides on our website. We also invite you to live tweet during the webinar today, using the hashtag racism and health. We will take as many questions as we can after our presentation.

Sheree Crute (02:42): I am now pleased to introduce our first speaker, Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones. Dr. Jones is currently an associate professor at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University. A past president of the American public health association, Dr. Jones research is some of the definitive work on racism in public health. She is going to help us to understand and show us how racism and privilege harm health in our society and the actions we can take to bring about change. Dr. Jones?

Camara Phyllis Jones (03:17): Thank you very much. I'm delighted to be part of this webinar. I would like to, but I'm going to be doing, sharing a story and then definition and some frameworks very quickly to help us understand that it's important to name racism and then we have to go beyond that and move to action.

Camara Phyllis Jones (03:38): The story that I'm going to tell you is one of my allegories based on my real life experience. This one that I call Dual Reality: A Restaurant Saga has the moral of racism exists. It's based on an experience I had when I was a first year medical student. One Saturday, I was in my apartment studying, because I was very diligent, very studious. About mid-afternoon, some friends came over. Rather than distracting me from my study, we all got to study a long and hard. It got late. We got hungry. I had no food in the apartment. Well, that was typical for me. My friends understood, so they were like, "Nevermind, Camara. Let's go into town and find something to eat." So we did. We went into town. We found a restaurant. We went in. We sat down. The menus were presented. We ordered our food. The food was served, and here we are eating, not a very remarkable story yet about racism.

Camara Phyllis Jones (04:42): As I sat there with my friends eating, I looked across the room. I noticed a sign. That sign was a startling revelation to me about racism. Now I've intrigued you, and you're like, "Okay, Dr. Jones, what does this sign say?" The sign said, "Open." Now I know I may have lost some of you, so let me recap what was going on. Here I was sitting in a restaurant eating. I looked across the room. I see a sign that says open. Well, I hadn't thought anything more about it. I would have assumed that other hungry people could walk in, sit down, order their food and eat. Because I knew something about the two sided nature of those signs, I recognize that now because of the hour, the restaurant was indeed closed and that firmly close and that other hungry people just a few feet away from me would not be able to come in, sit down, order their food and eat.

Camara Phyllis Jones (05:43): That's when I understood that racism structures open/closed signs in our society. That racism structures, if you will, a dual reality. For those who are sitting inside the restaurant at the table of opportunity eating and they look up and they see a sign that says open, they don't even recognize that there's a two sided sign going on, because it is difficult for any of us to recognize a system of inequity that privileges us.

Camara Phyllis Jones (06:11): For example, it is difficult for men to recognize male privilege and sexism. It's difficult for white Americans to recognize white privilege and racism. In fact, it's difficult for most Americans to recognize our American privilege in the global context. But those on the outside are very well aware that there's a two sided sign going on, because it's proclaimed closed to them, but they can look through the window and see people inside eating.

Camara Phyllis Jones (06:42): Back inside the restaurant, to those who ask is there really a two sided sign, does racism really exist, I say, I know it's hard for you to know when you only see open. In fact, that's part of your privilege, not to have to know, but once you do know, you can choose to act. It's not a scary thing to name racism. It's actually an empowering thing. It doesn't even compel you to act, but it does equip you to act so that if you care about those on the other side of this size, which is an if, but if you do, then you can even talk to the restaurant owner who is after all inside with you. You could say, "Restaurant owner, there are hungry people outside. Why don't you open the door? Let them come in. You will make more money, and Oh, the conversations we could have." Or maybe what you'll do is pass food through the window. Or maybe you'll try to tear down that sign or break through the door. But at least what you won't be doing is sitting back saying, "Huh? I wonder why those people don't just come on in and sit down and eat," because you understand something about the two sided nature of that sign.

Camara Phyllis Jones (07:45): Actually this story, it's useful to point out that yes, racism is creating two sides, multi sided sign, it's structuring dual or multifaceted realities. It's good to ask the question "How could people who are born inside the restaurant knows something about the two sided nature of that sign?" I once had a three hour conversation after asking that one question. There are many ways to know. It's also important for us this time to recognize that things in our society in the past nine weeks have made people who were born inside the restaurant, some of them have glimpsed the other side of that sign. Maybe the air conditioning went on high and caused the sign to flutter. Maybe a brick came through that window and caused a little breeze.

Camara Phyllis Jones (08:27): But for those people who are now understanding that there's a two sided sign going on, it is important for us to affirm that black lives matter. It's important for us to put the words together, structural racism or systemic racism. If we just say a thing, then six months from now, we are at risk of forgetting why we said that thing, because the somnolence of racism denial in our society is so seductive. I need to tell you is that we need to not just say a thing. You need to start acting to tear down the sign, to take the lock out, to take the door off the hinges. Because if you start acting, then you will not forget why you're acting.

Camara Phyllis Jones (09:08): I owe it's all a definition of racism. When I say the word racism, assume that I'm talking about a system. I'm not talking about an individual character flaw or a personal moral failing, or even a psychiatric illness, although it manifests in those ways. I'm talking about a system of power and a system of doing what is a system of structuring opportunity and assigning value. On what basis is the opportunity structured, and on what basis is the value assigned? It's based on the social interpretation of how one looks, which is what we call race.

Camara Phyllis Jones (09:41): What are the impact of this system of structuring opportunity and assigning value based on so-called race. But when we do talk about racism at all, we understand, most of us, that it unfairly disadvantages some individuals and communities. Every unfair disadvantage has its reciprocal unfair advantage. Racism is also unfairly advantaging other individuals and communities. That's the whole issue of unearned white privilege that we ever talked about, because it makes some people, especially some white people, uncomfortable. If you're feeling uncomfortable right now, because of me bringing unfairly advantages up, I used to say, "Shake it off. I'll tell you more stories." Now, what I say is, "If you're feeling uncomfortable, you need to lean into that discomfort because for all of us, the edge of our comfort is our growing edge."

Camara Phyllis Jones (10:30): There's a third impact of racism that many of us don't recognize. That is that racism actually saps the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources. When we affirm that black lives matter, it's not just the black lives matters. They're precious. They are genius. They are leadership. They are generosity and creativity and love. When we constrained black lives and indigenous lives and the lives of other people of color, either slowly by not vigorously investing in the full, excellent public education of all of our kids or quickly snuffing people out be leaning on their necks for eight minutes and 46 seconds, then it's not just a problem for the person whose genius has been lost or even for the family or the community. It's a problem because that loss is sapping the strength of the whole society through the waste of human resources.

Camara Phyllis Jones (11:18): I would like to be able to say that I would have time to share my Gardener's Tale allegory, which describes three levels of racism. I do not, but I highly recommended it. The moral of that story is that we must address structural racism, even as we also address personally mediated racism and internalized racism. Even if we don't address those, we must address structural racism, institutionalized racism if we want to set things right in our society. When we do the other levels will take care of themselves.

Camara Phyllis Jones (11:47): I also want to just share with you very briefly, a way of understanding, because it's important to name racism, but we must move to action. The next two steps in that trajectory are asking the question, "How is racism operating here?" And then organizing it, strategizing into act. How is racism operating here? It's a legitimate question. Racism is now a cloud or miasma we can't get a handle on. It is a system with identifiable and addressable mechanisms in our structures, policies, practices, norms, and values, where structures are the who, what, when and where of decision making, especially who's at the table and who's not, what sounds the agenda and what's not. Policies are the written how of decision making. Practices and norms are the unwritten how of decision making. Values are the why.

Camara Phyllis Jones (12:33): During the Q&A, I would love to take you through how that question can help us identify mechanisms of racism that are manifesting right now and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color. Just briefly, I want to give you one more thing. I define health equity in a three part definition, what is it, how do we get there, and how is it related to health disparities. Right now, I just want them to lift up three principles for achieving health equity, which are valuing all individuals and populations equally, recognizing and rectifying historical injustices and providing resources according to need.

Camara Phyllis Jones (13:07): Then what are we to do? What can we do today? Well, they need to actively look for evidence of twosided signs. Is there something differential going on by race, by language, by immigration status, by gender, by zip code. We need to burst through our bubbles, we all live in a bubble of experience, to experience our common humanity on the other side of town, to recognize it just across town there are people who are just as kind, funny, generous, hardworking, smart, as we are who are living in very different circumstances. We need to be interested in the stories of others and then believe the stories of others and finally, to join in the stories of others.

Camara Phyllis Jones (13:43): I'm so heartened by the mobilizations we're seeing right now in this protest movement and this association and this movement for black lives. We need to see the actions of, when we sit at this decision making table, we need to look around and say, "Who is not at this table who has an interest in this proceeding?" Our job is not just to represent their interests. Our job is to create space and find them a way to the table. Who's not at the table. What's not on the agenda. What policies are not in place. We need to reveal inaction in the face of me, because that is how structural racism most often manifest these days. All of the actions are not just on the part of those inside the restaurant, those of us on the outside need to know our power, to recognize that action is power and especially that collective action is power. I'm so delighted to have been able to share these quick thoughts. I turn the table back over to Sheree to bring on our next speaker. Thank you.

Sheree Crute (14:40): Thank you so much, Dr. Jones for sharing such insight and such a powerful presentation in our admittedly limited time. We look forward to hearing more from you during the Q&A session. Our next speaker is Dr. Derek Robinson, a vice president and chief medical officer of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois. Dr. Robinson will share with us how structural racism impacts a number of the social determinants of health and health care. He will also share some efforts underway at Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois to improve social determinants of health at the local level. Derek?

Derek Robinson (15:28): Thank you so much for the opportunity to be with you all today. I'm going to take a few minutes to build on the foundation of information shared by Dr. Jones and really do so with a local view. Let me start off by talking about one of the challenges that we face in Chicago and also in the state of Illinois. In Chicago, we have the unfortunate distinction of having the largest life expectancy gap between neighborhoods. It's the largest gap of any city in the United States. When we talk about health, it's important to also understand that because we have challenges in terms of historical segregation and housing both in the city of Chicago and cities across America, often we begin to see health factors correlate with race as well.

Derek Robinson (16:22): When you look at this slide here, it reflects where populations lived in the city of Chicago back in the 1960s. We know that place and race in our city, as well as in many other cities across the nation, have a close correlation with historic policies that were actually racist in intent and in impact. We know that many of those policies and intent that was codified in law has changed now, but we also recognize that the long arch of those policies extends from the 20th century, even into the 21st century.

Derek Robinson (16:58): The map that I just showed in blue was where a white Chicagoans live back in 1960, and in red is where you see predominantly African American populations in the city. When you look at this slide from 2010, you'll see that somethings have changed and some things have remained the same. A lot of the pink distribution is where a white citizens of the city live. The orange represents where the LatinX or Hispanic population is. Then you see the African American population in blue, again on the South and West sides of the city.

Derek Robinson (17:32): Now, the next, probably 10 slides I'm going to flip through are going to move through them pretty quickly. The point that I want to make is really a pattern which really shows that as we began to look at major indicators of health status, we see a strong correlation between place and poor health. Here we see a map that also shows plates and race. This gives us a chance to see longitudinally how the impact of policies and decisions put in place many years ago, a hundred years ago, still are having impact on the health of African Americans and other populations across the city.

Derek Robinson (18:10): This is more of a composite composite measure that looks at economic hardship. Again, we see that these are predominantly neighborhoods around the city, on the South and West side. Our next slide looks at children that have low childhood opportunity. Again, you see that in the same neighborhoods, these are predominantly African American and Hispanic neighborhoods. Again, as we look at environmental quality, these are where we have children who have high levels of lead in their blood, which we know contributes to cognitive delay and behavioral disorders, again, the same geographic distribution. When we evaluate unemployment, similar pattern. When we look at life expectancy, which we started off our conversation with, again, lower life expectancy in these communities. Then when we look at educational attainment, individuals that are adults who do not have a high school diploma, again, we see that in the same geographic distribution. Then finally, when we look at violence, we see high distribution of violence in some of these same communities on the South and West side of the city.

Derek Robinson (19:22): I added an additional slide in here just for context around infant mortality, because that is something that is really heartbreaking. We see it substantially, disproportionately affect the African American community. The next slide shows it even better. You'll see on the gold graph, the African American infant mortality rate is multiples that of the white infant mortality rate, which has been blue on this slide.

Derek Robinson (19:49): We now begin to tie some of these impacts also looking at wealth and income. This data I pulled from the report from the Chicago Community Trust. You see for every $100 of wealth that we have, white families in Chicago, black families have about $10. We really see that come into effect as we're looking at the resiliency of, financial resiliency of families today, dealing with COVID.

Derek Robinson (20:13): Now, when I pivot just back to the housing thing. We talked about the historic impact of discrimination in housing, which is codified in law, and many of those policies don't exist today. Yet we see that this analysis was just done by WBZ and published on June 3rd shows how banks lend money for residential property in the city of Chicago. It's looked at from 2012 to 2018, about $57 billion allocated for residential loans. You see that those are predominantly in the non-black, non-Hispanic communities. In fact, for every $1 that was invested in white neighborhoods, 12 cents within invested in black neighborhoods. That causes us to ask the question, "What's the impact of what policies that are in place today that impact lending?"

Derek Robinson (21:04): I'm going to switch over and talk to us a little bit about healthcare. Again, this last slide just notes that we in Chicago have the largest economic mobility gap within any city in the nation. The famous quote from Dr. Martin Luther King regarding inequality, and the fact that injustice in health is the most shocking and the most inhumane because it often results in physical death. He actually made that quote in Chicago in 1966.

Derek Robinson (21:31): Many of you who are familiar with major healthcare reports, you know that we've had some landmark reports that are pointed to discrimination in actual delivery of healthcare and the patients are treated differently based on their race and ethnicity. Part of what we're trying to do is take some actions based on the information that we are aware of today. We know that health disparities caused an additional $100 billion in excess direct medical costs each year. At the health plan, the state of Illinois, we spent over $25 billion on healthcare services for our members. We are rapidly moving down a value based care pathway. We have about a third of our membership in value based care programs and over a third of our spending there.

Derek Robinson (22:19): One of the things that we've done is figured out how do we begin to align the imperative to eliminate health disparities in our value based care programs as they move forward. In 2019, we've rolled out a training requirements for our physician groups. We have 80 IPAs that support our more than 600,000 members in our large HMO product, where we created incentives for providers to participate in training on implicit bias and cultural competency. We've then rolled this requirement out to our accountable care organizations, who were involved in a incentivized training this year. In subsequent years, we also asked these groups to stratify their quality data by race, ethnicity, and language, and then to focus on reduction and elimination and disparities, particularly in asthma, diabetes, and hypertension, and outlining years. We begin, again, to align these imperatives with financial incentives.

Derek Robinson (23:17): We've also partnered with the American Hospital Association to help incentivize more hospitals participating in the AHA Health Equity Pledge program. Several weeks ago we announced 13 awardees for a grant program of over a million dollars that would be divided amongst more than 13 hospitals to help support their efforts. We have also partnered with a number of organizations, including the American Heart Association, where we're investing in addressing food insecurity in parts of the South and West sides of the city. We have an example of two small businesses that have received investments, a 40 acres fresh market and the sweet potato patch.

Derek Robinson (23:55): We are also in the process of rolling out the Centering Pregnancy program, which is a program of the Centering Health Care Institute, which has demonstrated through evidence-based cure model of actually reducing disparities, racial and ethnic disparities in premature deliveries through prenatal care. We're actually helping a number of FQHCs get this program started up in neighborhoods where we see high levels of prematurity. We're also investing in housing programs that help support individuals who have both challenges with homelessness, as well as chronic medical conditions to help meet that need, provide wraparound services in housing to help them realize their best potential.

Derek Robinson (24:41): Now, one of the last areas I want to note here is that we are working collaboratively with our academic medical centers, teaching hospitals, as well as local and national organizations around improvement diversity in the physician workforce. We had our first major convening around this last year and had some exciting programs on the horizon in this particular space.

Derek Robinson (25:00): Then finally, in this era of COVID, I think is important also to note that we recognize that we have many communities that have disparate impact in terms of infection rates, hospitalization, and death rates. We have worked with over 75 community organizations over the last few months, donating over $1.5 million to help address any social determination. We've also distributed a number of a reusable masks, over 100,000, in these communities. We've supported initiatives at both the state and the local level to again, address some significant social challenges based in communities across the state, as well as supporting providers with respirator mask, over 150,000. Appreciate the opportunity to participate in today's panel and look forward to the Q&A.

Sheree Crute (25:48): Thank you so much Dr. Robinson for sharing some of the best practices and new ideas that Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Illinois is implementing to address the significant disparities in the Chicago region, which I think is also a good model for other urban areas. Now we would like to welcome Tiffany Netters, MPA. Tiffany is the executive director of 504 HealthNet in New Orleans, Louisiana. Ms. Netters is an expert in addressing health disparities and their impact at the community and grassroots level. She works with more than 17 federally qualified health centers and approximately 70 community organizations in New Orleans addressing the needs of uninsured populations and those are Medicaid. Tiffany?

Tiffany Netters (26:39): Thank you. Hello everyone. I wouldn't like to take you all down New Orleans now. The objective from my presentation is to give you all background and context for the work that we do at 504 HealthNet that leads to my ideas that I will share with you around community level solutions to address systematic racism from within health care. I'll also highlight some projects that we feel like have the potential for a major impact on the black community and the greater New Orleans area. I'll offer an outline of the community level solutions that we use to make positive change in the South to address systematic racism from a health equity lens for hopefully your consideration in your work.

Tiffany Netters (27:29): 504 HealthNet was born in the aftermath of hurricane Katrina as a collaboration of the local community health centers, the state health department, and the city of New Orleans to rebuild the primary care system in the area. Our mission is to improve access to care for all regardless of their ability to pay and to provide support to integrate it and coordinate a network of healthcare providers in the area. We're all working to achieve common goals that I'll share with you shortly. Our membership does consists of 27 healthcare organizations and government agencies who operate over 75 clinics across the different neighborhoods in the Orleans, Jefferson, Plaquemines, St. Bernard, and St. Charles Parishes. These clinics are all dedicated to serving patients no matter their income insurance status or social status.

Tiffany Netters (28:27): Our greatest value is in our members of community health centers and our governmental agencies. Right now, I want to highlight the 13 member organizations that are federally qualified health centers or FQHC. These FQHCs are safety net providers that typically provide primary care services that are provided through outpatient clinics.

Tiffany Netters (29:02): Community health centers are vital health care safety net. As an advocate for these health centers, I believe they should be recognized and supported as a priority community level solution and addressing systemic racism. They were born in the 1960s from the war on poverty and the social justice movement at the time when there were many communities, especially blacks who are not being provided care by mainstream healthcare system. In the 1990s, the federal government started to fund community health centers, deeming them federally qualified if they met certain requirements such as serving a designated medically underserved area populations, offering a sliding fee scale to persons whose income is below 200% of the federal poverty level. They're also governed by a board of directors whom the majority of the members receive care from the organization.

Tiffany Netters (29:59): These organizations started within the health care system are community driven. They also provide comprehensive services and provide culturally competent care because our healthcare providers are dedicated to the community. I feel like the most culturally competent providers are those who are from the community, that look like the community and who can relate to the patient's circumstances. We have that in the federally qualified health centers. As far as who we serve within our health centers in the area, there's over 190,000 patients that come into the doors of the community health centers, majority are African American, and a majority of our patients are also on Medicaid.

Tiffany Netters (30:52): As a collaborative group, 504 HealthNet uses the collective impact model as a framework for how we organize and work together. 504 HealthNet serves as the backbone coordinating organization. It coordinates a common agenda with three service pillars of connect, learn and advocate. Under each pillar, we have goals for ensuring access to high quality, primary care and behavioral health for all, especially the underserved.

Tiffany Netters (31:30): Together as a collective, every year, we come up with our strategy and action plan. Our work is organized under those three pillars that I mentioned. Our action plan as shown here, is focused on community engagement, health systems, capacity building, and policy advocacy for health systems change and health equity. As you see, we put connect first, because we build upon what we hear from the community and to our learn initiatives and advocacy efforts. Health equity, a belief in that everyone should have the opportunity to live their happiest, healthiest life is a core value around work and is embedded in our strategy. We understand that we as public health care professionals have to be close as possible to those that we're trying to serve. We focused on building partnerships with the patients of our health center members to better engage them in our programming and policy advocacy work. Ultimately, we do believe that the true power and solutions are within the community. Again, we use the data and information that we first gathered from our community listening sessions and our advocacy council to inform our programming.

Tiffany Netters (32:47): Now I would like to share with all two examples of our community engagement initiatives that has potential impact, as I said, on the black community. Our initiatives called the New Orleans Healthy Hospitality Initiative was born out of a local movement of social service workers who had demands that the city use a portion of the hotel tax to provide healthcare to workers. Please note that more than 50% of the workers in the city are black, and many of them are not offered benefits and healthcare from their employers for various reasons.

Tiffany Netters (33:21): The process by work is during a board meeting of the New Orleans tourism marketing corporation in May of 2018 initiated citywide conversations about what is happening regarding healthcare for these workers. We were able to present to them our membership structure and talk about our sliding fee scales, and so the preparation was like, "Well, it seems like the infrastructure is there. How come no one knows about it?" We work with the New Orleans Tourism Marketing Corporation who has those resources to get the word out to really develop a major community engagement and marketing campaign that would reach the workers and address some of the barriers that we heard that they had from our listening session. That initiative is still going on. We just launched last eight August. Currently there's lots of movement still with hospitality workers, addressing racism, addressing healthcare, and economic justice.

Tiffany Netters (34:25): The next example of initiative I want to share with you is around us trying to connect formerly incarcerated residents to healthcare. Louisiana is suffering from dual academics right now when it comes to HIV and incarceration. About 66% of the state's prison and jail population is black. We have been able to partner with one of our member clinics, the FIT clinic, or Formerly Incarcerated Transitions clinic and the National Transitions Clinic Network to secure funding from Gilead Compass Initiatives to fund a pilot program where we can build capacity of our community health centers to provide socially tailored, trauma informed healthcare services to residents and reentry. We're also looking at those barriers that they're having and working with systems like our health department and Medicaid program to really increase access for the population.

Tiffany Netters (35:25): Like everyone else, we have experienced lots of chaos now across our communities due to COVID-19. At the start of this pandemic, we learned very quickly that our community health centers were not considered a tier one for the federal emergency management plan, and they would not have access to the national stockpile for PPE. We quickly stopped partnerships from private donors who help to secure and distribute PPE to our frontline staff. For me, this was a red flag and lots of questions were coming up. We were wondering why wouldn't our neighborhood safety net clinics who are in the community with those in most need not get the resources from the federal and state government. There is so much confusion in the community and amongst our providers about factual information and also where testing resources were.

Tiffany Netters (36:17): And so as a small grassroots organization, we worked with our partners to acquire PPE and emergency resources for our staff. We developed communications channels for clear factual information for our patients, providers and community members. We started linking the needs of patients and the most vulnerable to resources such as housing, any emergency funding. We have been advocating for better coordination of our staffing and human resources across the system. We will continue to advocate for our longterm strategy for the next emergency and trying to get our community health centers listed as tier one.

Tiffany Netters (37:04): Now I'd like to provide an outline or a recap of the specific efforts we are implementing in our programming to adjust systemic racism as a community based organization. As a Louisiana native, I will say that we are still plagued by slavery and the Jim Crow era. All of our systems are stained. From our reputation of fat politics, our high poverty rates, ongoing national disasters, and being one of the least healthiest states in America, we see that our systems are set up for our failures, specifically the black community's failure.

Tiffany Netters (37:50): As a small grassroots organization, we work to leverage our members and partners to implement solutions within the healthcare system, because that's something that we can control as a small group. We do strive for authentic community engagement when it comes to our connect services. We serve as community clinical linkage and support the workforce, looking at navigators and community health workers. Our community needs to see us, so we try to ensure that our providers, our community health workers, our peers of our community, that we're trying to serve. We host community listening sessions and format programming. At the start of our programming and decision making, we provide community engagement trainings for health care providers within the system. We support consumer advocacy infrastructure to get that feedback from our patients and those on Medicaid. Then we connect to other community nonprofit service providers for coordination of care and linkages to care, specifically when it comes to housing and food security.

Tiffany Netters (38:58): Under our learn pillars, that's our capacity building of the safety net. These activities we do consider internal to the healthcare system. We provide quality improvement initiatives where there's ongoing training and technical assistance. We also have done implicit bias trainings for our providers. We create feedback loops for the healthcare system to incorporate the information that we hear from the community. Then we do many grant incentives to ensure that our providers and the organizations strive for ... I'm sorry. I just lost my slide. [inaudible 00:39:42]. Yeah, still there.

Sheree Crute (39:48): Yes, I hear you.

Camara Phyllis Jones (39:50): Yes, we hear you.

Tiffany Netters (39:51): Sorry all. I just had technical difficulties with my computer. Could somebody click next slide for me? For our advocates, advocacy pillar, we are heavily involved in many coalitions and work to build relationships with our policymakers, because we know that healthcare policies serve as a key intervention for public health and core strategies for making changes. We work to secure resources for the infrastructure, workforce and operations of our community health centers. Like I said earlier, we will be advocating for health centers to be listed in tier one for federal and state emergency management. We develop promising practices from models of care using community health workers and patient navigators. We advocate for policy and systems change for racial and economic justice, specifically right now we're working in Louisiana on minimum wage increase and paid sick leave. Then we support policies that increase access to health insurance, also strong advocates for our Medicaid expansion and employee benefits. We are continuously looking for opportunities to address social determinants of health. Will somebody click next slide for me?

Tiffany Netters (41:12): In closing, this is just something I'm always thinking about. If our systems are set up for our failure, let us create better systems. I hope that I provided you all with some insight in how community organizations can impact healthcare and promote health equity, and hopefully have given you some ideas for your work. Thank you.

Sheree Crute (41:35): Thank you so much, Tiffany, for giving us a comprehensive perspective on how to work across underserved communities and at the grassroots level. We're excited to engage in questions right now. People have been submitting questions all week and many are very complex. What we've tried to do is combine some of those questions, so that we can address as many issues as possible.

Sheree Crute (42:02): Our first question, I'm going to direct to Dr. Jones, what is the scientific evidence, one of our listeners wanted to know, between racism and racial discrimination and poor health? I would add that that question was also asked, especially in the context of COVID-19. Dr. Jones?

Camara Phyllis Jones (42:26): Oh, so there's so many levels to answer that question. The first thing is that we document race associated differences in health outcomes across the board, but we need to ask what are we measuring when we measure that variable, race. Race is just a rough proxy for social class, rougher for culture, meaningless for genes, but it precisely captures the social interpretation of how one looks in a race conscious society. That is the same race that a medical admitting clerk checks off for a person that becomes part of a health statistic is the same race that a taxi driver notices or a police officer or a judge in a courtroom or a teacher in a classroom. That race is actually picking up the impact of racism.

Camara Phyllis Jones (43:07): At the CDC, we actually had a six question reactions to race module where we asked about that socially assigned race. How do other people usually classify you in this country? Would you say white, black, Hispanic, Native American, et cetera, et cetera, not making any artificial distinction between so-called ethnicity, being Hispanic or Latino and the others as so-called race. In our paper that we published in 2008, in Ethnicity and Disease, we found that even for people who self identified as a non-white race, it's other people usually classified them as white, which was quite common if you self identified as Hispanic or Latino, also common if you self identified as American Indian, or Alaska native, and also common, if you said that you were more than one race. Those people who self identified in a non-white group, but we're usually classified by others as whites, their health was significantly better than other members of that group and indistinguishable statistically from those who self identified as white and were usually classified by others as white.

Camara Phyllis Jones (44:13): Of course, there are many, many studies that have looked at mental health outcomes, cardiovascular outcomes. All across the board, there are excellent reviews, one recently by Dr. David Williams and Dr. Lisa Cooper. So there are many, many studies now over two decades that are documenting that. That's the first part of it is that what the variable race map measures is actually the impacts of racism, so that when we see these race associated differences, well, that's what we're measuring. Now I've forgotten the other two places I wanted to take that.

Camara Phyllis Jones (44:46): Oh, with COVID-19. Here's the short story about what's happening with COVID-19. Black people and other indigenous people and other people of color are more likely to get infected because we are more exposed and less protected. That's the first step. Then once infected, we're more likely to die, because we are more burdened by chronic diseases with less access to health care. The more exposed has to do with being in the frontline jobs, which has to do with living in disinvested, racially segregated communities, as demonstrated by Dr. Robinson with less access to healthy foods, less access to quality healthcare, as Tiffany Netters talked about, poisoned air, no green space, all of that. The main thing about living in those disinvested communities is crowded housing, more of that, but then less of ...

Camara Phyllis Jones (45:46): Public schools are financed based on local property taxes, then you have poorly funded schools, often results in a poor educational outcome and another generation loss and that results in the occupational segregation that we see, which is why you're more reflected in frontline jobs, you're more likely to be in jails and prisons, more likely to be unhealthy, more exposed. Less detected because we're really not as valued, don't have access to the PPE, even the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has not yet promulgated workplace standards, safety standards, including how far workers need to be in the meat packing plant, how should the screening be done, how should the PPE be made available like that? Then when you get to the ...

Camara Phyllis Jones (46:32): That's why we're more exposed and less protected. We're more infected. Then because we're living in these disinvested communities with less access, we're more burdened by chronic diseases and less access to healthcare that's been covered by others. I'm going to stop talking now. Yeah, we have it. There was one other thing I wanted to say, but other people would have answers to that question.

Sheree Crute (46:57): Thank you, Dr. Jones. Dr. Robinson with several questions about how to about providers. Can you speak a bit more to the incentives you may have provided to entice providers, IPAs, ACOs, and others to participate in implicit bias training, as well as what type of behavioral or other changes you would recommend for providers who want to reduce the impact of systemic racism in the people they serve?

Camara Phyllis Jones (47:37): Sure. Thanks. Thanks for the question. There's not an easy, not an easy task. I think there are a couple of factors that come into play, especially doing this authentically. One is humility, education measurement and incentives, I think humility first, because you start off with the oath to first do no harm. Most providers are going to approach this discussion from a vantage point of always doing good and having a mindset that we will treat everybody well, without any mal intent or any discrimination based on race or gender.

Camara Phyllis Jones (48:12): The second I think is around education, so what do we need to support providers with in terms of understanding implicit bias, that it's not bad, that we all have it, it's part of our life experience, and also to strengthen our education around racism that it's not this dichotomy of good and bad, and that also we need to better understand the difference between intent and impact and the need to look at both of those.

Camara Phyllis Jones (48:38): The measurement piece is important because you need to be able to see where differences in healthcare provided may stratify by race and ethnicity or gender. Then incentives, so we've got to make it a business case, not just this moral imperative to do the right thing. I think the work that we've done in working with our providers, I think begins to model out how you make this part of the business case. Patients bring their own lived experiences to they encounter as well, and so we have to also ensure that we're equipping our providers with the tools to try to meet patients where they are, understand and acknowledge their valid experiences and perspectives and see how we can bridge the two together to achieve better health outcomes for these populations,

Sheree Crute (49:28): Trisha Netters, we have many questions about the role that state Medicaid agencies can or should play in addressing systemic racism and reducing health disparities. Can you speak to that a little bit from your experience what Medicaid's role might be at this time?

Tiffany Netters (49:49): Sure. As a community advocate, I could speak to that. I really feel like thinking about what Dr. Robinson talked about with the value based care movement and how a lot of programs with Medicaid, going more that way to value based care, really using the health equity lens and integrating that into how providers are incentivized and trained and looking at outcomes. Also, when it comes to provide a reimbursement being more open to providers, being more engaged in the outward facing community work as within the healthcare system, providing incentives and reimbursements for the healthcare to be more involved in the different movements, such as educational reform or economic justice movements, really getting to the root causes of a lot of the bad chronic disease outcomes that are showing up in the provider's offices, giving them the opportunity to address those beyond just medicine. I'll stop there.

Sheree Crute (51:03): Okay. We have a number of questions about trust that are perhaps based in historical perspectives on how African Americans have been treated in the medical system. I'm not sure, Dr. Jones or Tiffany, either one of you, Derek, if any of you would like to address. We have people have asked from that community perspective and provider perspective, how can you build trust and thereby encourage people to seek available care and access.

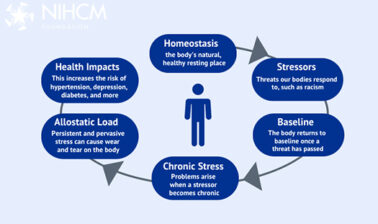

Camara Phyllis Jones (51:35): This is Camara. I would say in order to build trust, you have to be trustworthy. Historical things have happened and things are happening every day, even in terms of how people are sent back from hospitals to die at home without a COVID test, very early on in the pandemic, probably still happening. I think that to the extent that health systems are trustworthy, then people will start trusting them. The other thing I wanted to say, building on what both Derek and Tiffany were talking about is we all recognize that health is not created within the health sector. I just wanted to throw that in there. Even though we're talking about health, the impact of systemic racism and how it structures our opportunities and how it differentially values us. We need to go in the healthcare system, yes, and with trust and all that, but the most profound impacts of racism happen without bias, without any specific individual action. It that happens through inaction in the face of need. Individuals need and the system needs to be more trustworthy, but we need to create better, we need to invest in all of our communities and value all of us equally.

Sheree Crute (52:56): Thank you.

Tiffany Netters (52:56): This is Tiffany. I'll add to that if I can.

Sheree Crute (52:58): Sure, go on.

Tiffany Netters (53:02): Building on being trustworthy, I think, an important thing that we've realized is it's based on communities having advocates and partners with us as an organization within healthcare. I think that's why it's so important for community health workers and peer supporters to be acknowledged as workforce within the healthcare system, because they are from the community and can help spread the message that these, that our organizations are trustworthy. We find out word of mouth is a very powerful vehicle to get communication messages out to the community.

Sheree Crute (53:40): Thank you. Dr. Jones, we have a question about how telemedicine and perhaps other methodologies are being used to fill gaps in, especially in mental health and substance use disorders during the pandemic for urban and other underserved patients. Would you be able to address that?

Camara Phyllis Jones (54:04): Well, yes, it's being used for people who can access those services, but even in urban areas, there are many people who cannot financially access broadband and certainly rural communities where telemedicine is even more necessary, they don't have access. I have felt that intensely myself because just for one week here I am in a city and unable to, my internet went out at home. I will just say that before we roll out big interventions, we need to provide resources according to meet. If we're going to roll out an intervention, we need to pay attention, is this intervention going to create larger disparities in terms of access?

Sheree Crute (54:51): Dr. Robinson, did you want to add to that? I know you might use telemedicine or similar methodology.

Derek Robinson (54:58): Sure. I would echo the sentiments says that Dr. Jones shared. I know there was a study or at least a news report out of California, a few weeks back where one of the academic practices looked at the demographics of their patients pre-pandemic and or an intro pandemic with the introduction of more widespread telemedicine. They actually saw a drop in their diverse population as they were moving towards telemedicine. We do have to be attentive to the potential digital divide that can occur both from a urban perspective, as well as race and ethnicity and socioeconomic perspective. We see similar challenges as we think about education and remote learning, so you just transpose that on top of healthcare and you'd see some similar parallels.

Sheree Crute (55:53): The last question is do you have recommendations for upstream strategies for health disparities in particular that we have not highlighted that you think are particularly important today?

Camara Phyllis Jones (56:09): Well, this is Camara. I'll jump in first. I think that we need to not let racism and anti-racism fall off of the agenda. We need to all engage in a national campaign against racism and recognizing it's not a 10 year campaign or even a one generation campaign. It will have three tasks, name racism, to say the whole word, because if you don't say the word racism in the context of widespread denial, you're complicit with the denial, then to ask, how is racism operating here to identify the possible leverage for intervention in our decision making processes, and then organize and strategize to act. The top three, the top four agenda items I have in the policy agenda are reparations to descendants of Africans enslaved in the US, the decarceration, and some people talk about abolition of prisons. The third would be massive investments in communities of color, addressing housing and doing wealth building and schools and green space and environmental clean up and the like. With that massive investment and now make it a fourth one, massive investment around families and children, early childhood education and all. We would know we would have been successful when the term disadvantaged child had no meaning, that we couldn't even imagine a child being born into or finding themselves at a disadvantage.

Sheree Crute (57:30): Thank you. Dr. Robinson, did you want to add? Or Tiffany? We have a couple of minutes.

Derek Robinson (57:36): Sure, I'll add. It's, again, nice to be on a stage with these two experts. What I would add to that is a focus in the area of increasing diversity in the physician workforce. I touched it just barely earlier, but I would think it's worth noting in this conversation that the under representation of African Americans, both in the physician workforce and more broadly, and then as you drill down to specific specialties, it's really significant. This was one of the areas that our healthcare system actually has the ability to move forward. I think it's something that we need to highlight and really move the needle on as one of the mechanisms to have an endurable approach to reducing and eliminating disparities. I would agree that many of the drivers of health are outside of the doctor's office and the walls of the hospital and drivers of disparities that we're discussing.

Sheree Crute (58:37): Thank you. Well, unfortunately we are out of time at this time, but I want to thank this amazing panel of speakers. Thank you all for offering so much insight and so quickly in our small space of time. I appreciate your taking time out of your busy schedule to be with us today. Please take a moment, if you are listening in to share your feedback from the event by completing a brief survey that can be found on the bottom of your screen. Also, please check out the other resources on our NIHCM website.

Sheree Crute (59:12): In early September, you will receive an invitation to our next webinar in the series, which will be looking at Latino and Hispanic communities and some of the disparities that are impacting people there in the United States. We also have an upcoming webinar on racism and environmental health. Please, don't forget to share your opinions. Again, thank you all for joining us today and thank our speakers. Everyone stay safe.

Presentations

Naming Racism and Moving to Action

Camara Phyllis Jones, MD, MPH, PhD

Emory University; Morehouse School of Medicine

Local Insights and Efforts to Eliminate Health Disparities

Derek Robinson, MD, MBA, FACEP, CHCQM

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois

Community-level Solutions to Address Systemic Racism

Tiffany Netters, MPA, PMP

504 HealthNet

More Related Content

See More on: Health Equity | Coronavirus