Expert Voices

The Outlook for Reforming Payments to Graduate Medical Education

By: Gail R. Wilensky, PhD, Senior Fellow, Project HOPE

Each year, more than $15 billion of tax-payers’ money is spent to support physicians in residency training. About one-third of this amount comes from Medicaid, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Health Resources and Services Administration. The remaining nearly $10 billion flows through the Medicare program, primarily to academic medical centers via a complex system of direct graduate medical education (DGME) payments for residents in approved training positions and indirect medical education (IME) payments intended to compensate teaching hospitals for the added costs of caring for Medicare beneficiaries in a training environment. With an investment of this size it is fair to ask whether this public money is being well spent, especially given oft-voiced concerns about specialty and geographic imbalances, insufficient workforce diversity and readiness to practice in today’s delivery systems. Indeed, one could even question why Medicare plays such an outsized role in training our nation’s physicians and whether public support is warranted at this level or at all.

It was within this context that the Institute of Medicine (IOM) convened a 21-member committee in 2012 to assess our current GME system. Dr. Donald Berwick and I – two former administrators of Medicare and Medicaid under Democratic and Republican Administrations – co-chaired the committee. Most of the committee members were academic medical and nursing leaders and, thus, beneficiaries of the government’s support of GME. Our July 2014 report contained five recommendations for a bold restructuring of GME financing.1 In this essay, I explain the recommendations and provide an update on stakeholder reactions as well as potential Congressional interest in tackling changes to GME policy.

The IOM Recommendations

The IOM committee discussed at great length the unusual role that the federal government and, in particular, Medicare have in supporting GME. Ultimately, we recommended that Medicare maintain its total level of DGME plus IME funding for the next ten years (adjusted for inflation), while gradually phasing in performance-based payments designed to develop a more optimal physician workforce. Committee members agreed that ongoing Medicare financing over a transition period would provide the stability and leverage needed to effect desired changes in the GME system.

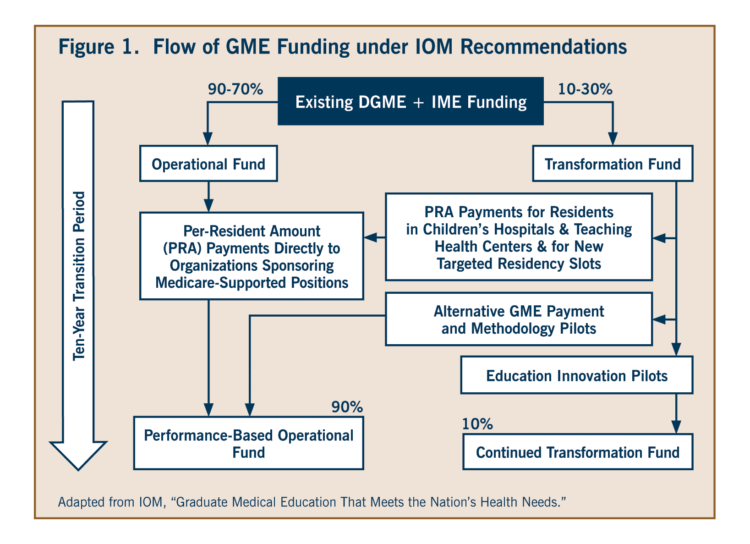

For this revamped system, the committee recommended consolidating Medicare GME resources into a single fund with two subsidiary components: (1) an Operational Fund that continues to support existing and future Medicare funded training positions and (2) a Transformation Fund to support innovations in how GME funding is used (Figure 1). These innovations could range from research to develop metrics for judging training program performance to testing new ways to distribute residency funding beyond the hospital setting or to address geographic or specialty shortages. The committee assumed that initially almost all of the resources would stay with the Operational Fund but that the allocation to the Transformation Fund would gradually grow as training programs develop the capacity to undertake innovation pilots. Then, as successful innovations are adopted, related funds would move back into the Operational Fund.

To bring more rationality to the GME financing system and provide guidance in its evolution, we recommended creating a GME Policy Council within the Office of the HHS Secretary. This council would develop a strategic plan for GME, identify the types of research to be sponsored by the Transformation Fund and coordinate activities among groups accrediting and certifying residency programs. On a parallel front, we called for a new GME center within CMS to oversee the distribution of funds in accord with Policy Council guidelines.

Our fourth recommendation addressed the complexity and opacity of the current mix of DGME and IME payments by calling for the combination of these funding streams into a single national, geographically adjusted payment per resident. These payments would be made directly to GME sponsoring organizations and, over time, would move to a performance-based system informed by the Transformation Fund pilots.

Fifth, recognizing that Medicaid pays about $4 billion to support GME each year, we recommended that states continue to be allowed to use Medicaid funds for GME but that the same level of accountability and transparency be required for Medicaid as is proposed for Medicare.

Because Medicare’s system of financing GME has not changed fundamentally in the last 30 years, the committee recognized that the changes we put forth will be disruptive to the teaching hospitals and other sponsoring organizations that have become used to receiving these monies year after year. The ten-year phased-in implementation period we advanced is intended to minimize disruptions. It is only after this period that an additional determination should be made about the appropriateness of continued federal funding of GME.

Other Approaches to GME Reform

The IOM is not alone in recommending significant changes to Medicare GME support. In contrast to our call to maintain current funding levels, the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform recommended reducing the currently legislated IME payment amounts by 60 percent and limiting the variation in DGME payments.2 The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) also recommended cutting IME payments by more than half (about $3.5 billion) and redirecting these funds to establish a performance-based incentive program.3 While this amount is similar to what the IOM recommended for the Transformation Fund, there would be substantially less reallocation of funds under Med-PAC’s approach because they did not change the distribution of remaining GME funds.

Developments Since the IOM Report

The representatives of medical colleges (AAMC), organized medicine (AMA) and hospitals (AHA) responded to the IOM report immediately and more harshly than they had responded to previous reports recommending payment reductions and/or redistributions. Their key objections focused on the lack of agreement about a potential future physician shortage and its implied need for additional funding and on the refocusing of training opportunities away from the inpatient setting.

Other groups, including the Association of Academic Health Centers and several national and regional groups associated with primary care have been generally supportive of our work, applauding the report’s recognition of the mismatch between the increasing specialization in training and the needs of an aging population as well as the committee’s emphasis on training physicians to deliver patient-centered, value-oriented care.

Moving forward on the IOM recommendations will generally require Congressional legislation. Last December, a bipartisan group of eight representatives on the House Energy and Commerce committee asked stakeholders to comment on the IOM re-port and on other approaches to GME reform. Comments were due in mid-January of this year. The presumption is that the Energy and Commerce committee will hold a hearing at some point and invite the stakeholders to discuss their submitted comments. No date for such a hearing has yet been announced though. Even less certain is whether any funded legislation to modify GME payments will be put forth, or what that legislation might look like. Special interests are vocal and powerful on this contentious issue, and the recent passage of the “Doc Fix” legislation means that a legislative vehicle that might have contained GME reforms is no longer available.

Debates About Future MD Shortages

One area where the IOM parted ways with almost all of the medical groups is in its assessment of the likelihood of a future physician shortage. For example, recently updated estimates from the AAMC project a shortage of 46,000 to 90,000 physicians by 2025.4 GME stakeholders use such projections not only to argue against reductions in GME funding but also to press for more federally funded residency positions.

While the committee was not directed to consider this issue, assumptions about potential shortages or surpluses were part of our deliberations. We concluded that attempts to forecast physician supply and demand, both in the aggregate and by broad specialty types, have been singularly unsuccessful in the past. In fact, past projections have not always been even directionally correct. The biggest problem is that most models use existing physician-to-population ratios to project the number and type of physicians needed in the future. Implicitly this approach assumes that the current way of producing medical care is the only way to do so. Rarely a good assumption, it makes even less sense than usual in this era of rapid changes to how we are delivering and paying for care.

Furthermore, our supply of physicians has already been increasing rapidly, even without additional federal funding. Medical school enrollment rose 28 percent between 2003 and 2012 and the number of residents rose by about 20 percent despite the cap on Medicare funded positions.5 Increased numbers will not, however, automatically produce a better specialty or geographic mix of physicians.

In the end, leveraging a full decade of continued Medicare GME support (at upwards of $100 billion) as recommended by the IOM while figuring out how to introduce far more flexibility and deliberateness into training pro-grams will be more constructive than producing yet another round of shortage projections that are far more likely to be incorrect than correct.

- Institute of Medicine. Graduate Medical Education that Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, July 2014.

- National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. The Moment of Truth: Report of the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform. December 2010.

- Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Aligning Incentives in Medicare. June 2010.

- IHS Inc., The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2013 to 2025. Prepared for the AAMC. March 2015.

- Chandra A, Khullar D, Wilensky GR. “The Economics of Graduate Medical Education.” New England Journal of Medicine, 370:2357-60. 2014.

More Related Content

See More on: Cost & Quality | Health Care Coverage